[addtoany]

[space height=”10″]

Amy Milne (AM): This is Amy Milne. Today’s date is October 21, 2010 and it is 10:27 a.m. and I’m conducting an interview with Alice Helms for the Quilters’ S.O.S.–Save Our Stories, a project of The Alliance for American Quilts. And we’re here in the Alliance office today in Asheville, North Carolina. Alice tell me about the quilt you brought today.

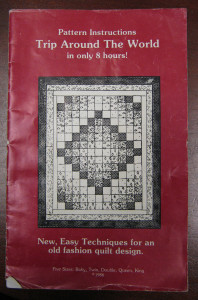

Alice Helms (AH): This is the second quilt I ever made. It was made in 1989. I made it for my nephew Justin Rahm, my sister’s son. It’s a crib quilt. It’s about 38 inches by 52 inches. It is a Trip Around the World pattern. It’s made with calico fabrics that are primary colors. My sister had requested primary colors. That was going to be the theme for his room. So that’s what I used and it is hand quilted sparsely. It’s the second quilt I ever made–the first one was tied. So this was my first attempt at hand quilting. And I’m wondering how I did that when I look at it now, because it’s very–the fabric is very loose. I wonder if I even basted it, or I know later when I would hand quilt I would use a hoop, but I wonder it this was even stretched on a hoop because the fabric is kind of loose and puckery which has caused a lot of wrinkling and wearing. It’s quite worn out. It looks much older than 21 years old, to me. And in fact, at some point–I want to say Justin was maybe 3 years old or 4 years old–the binding wore out. I think that in the original quilt there was no quilting in the border and the binding just wore out. And my sister called me up and she said, ‘You know he loves this quilt and it’s been washed and washed and washed. And he drags it around. And now I’m getting worried because the binding is actually just opened up. And his little fingers and toes get in there and it’s just making it worse,’ and ‘What can we do?’ So she was living–they were living in Atlanta, Georgia and I was living in Connecticut. So I said, ‘Well send it back to me and I’ll see if I can fix it, maybe I can replace the binding.’ So she had to have a little talk with Justin and say, ‘You know, we’re going to pack up the quilt and we’re going to send it back to Aunt Alice in Connecticut and she’s going to fix it. And then when it comes back it’ll be all new and, you know, it’ll be better.’ And I guess he was a little apprehensive about having his quilt [inaudible]. But they sent it off and when I got it I was remembering that I just replaced the binding–but now that I look at it, it appears that I replaced the whole border and just did a sort of front to back binding on it and quilted it. And then I sent it back to him. And a funny story that came out of that was a couple years later my sister called me up and she said, ‘Justin’s stuffed Barney has a hole in it. One of the seams is opening up.’ Now Barney is a dinosaur that was a very popular children’s TV show at that time–maybe it still is, I don’t even know–but at that time a very popular TV show and people would get this stuffed Barney stuffed animal and he had one and I guess the seam was opening up. So she said, ‘The seam’s opening up on his Barney and you know he’s kind of upset about it,’ and ‘Do you think you can fix it?’ And I said, ‘Betsy you know how to sew, you can sew a seam.’ And she said, ‘No. He thinks that you’re the one–you’re the only one who can fix it. So he’s willing to give it up. He’s willing to put it in a box and mail it back to Connecticut for you to fix it.’ [AM gasps in awe.] So [inaudible] came in a little box and I went out and I bought a spool of purple thread and stitched Barney up. It was probably like a one-inch [AM laughs.] seam that was open but the stuffing was starting to come out. And I sent it back and who knows–anyway, Justin has had many quilts from me over the years–he’s my only nephew. And he had this crib quilt, he had a quilt that was a single bed size that I made for him when he was 8 or 9 maybe. And then around the time he graduated from high school he wanted a–or his parents wanted him to have a t-shirt quilt. So I took his t-shirts and made him a quilt with those. Now at the moment all these quilts sit in a closet–he’s in college now, a senior in college. But I’m hoping, you know, some day he’ll have them and use them. You know maybe when he has his own family. But this pattern I got–I–I wanted to quilt for many years. And I’ve been fascinated with quilts and I wanted to make a quilt but it was a little daunting how to get started. And I’d seen an article in, I think it was in one of the women’s magazines, about this quilt-in-a-day technique. And it was an article about these women that all went to some high school gym at 9:00 in the morning and they learned this technique and at 5:00 in the afternoon they walked out with quilts all made. And I thought, ‘Wow, you know, I could do that.’ So they had a place you could, you know, send in a dollar or two dollars and you could get this pamphlet on how to do this technique. And that’s what this is. And not that I did it in one day, the first one I made–the first quilt I made was also this Trip Around the World and then this baby quilt was the Trip Around the World quilt-in-a-day pattern. And I think I made a couple others after that too. But it just involved, you know, cutting your fabric in strips and sewing the strips together and then slicing those to make the squares. But of course when I made this I didn’t have a rotary cutter, I had never heard of a rotary cutter. So it was laying the fabric out and I think I used a yard stick to kind of measure and draw lines and cut it with the scissors and sew it together. But I was quite proud of myself at the time. I was pleased as punch when [AM and AH laugh.] I finished the first one. And now when I look at it you know it’s just humbling. [AM laughs.]

AM: Why do you say that?

AH: Because it’s–it’s so poorly done. [AM and AH laugh.] And it’s just–it’s inadequately quilted as I was saying before. And I think–you know, although it–although you learn from that because you realize why quilting needs to be a certain minimum distance apart to maintain the quilt. And there are places where I can see the seams started to open up. And I wonder about that because it was actually stitched on a machine. But there are places where I’ve just kind of taken sloppy stitches to correct that. I probably did that when the quilt came back to me for repair.

AM: So when did you get the quilt back?

AH: So he–this was his baby quilt. And then when he was finished–

AM: I mean did you get it back for the interview or–or do you have them, or does he still have them? You said they were in a closet.

AH: Right. I got it back for the interview, yeah. I hadn’t seen it in years. And I was sort of thinking about what quilt I could really talk about and this was the one. And I have to say I was shocked when I saw it. [AM and AH laugh.] I remembered it differently. [AM and AH continue laughing.]

AM: Do you think this is still your–you’re shocked by the workmanship and how different it is from what you do now. But what about the style, are you still doing traditional patterns? And do you still get pattern books and follow them? I mean what other ways have you–do you see this as being, you know, representative of the changes that have occurred to you?

AH: The fabric. The calico fabrics.

AM: Uh huh.

AH: I don’t know if we even really see these anymore.

AM: True.

AH: If they’re in the quilt shops now, I certainly don’t notice them. So I think that’s a big, big difference. But really,the way I remember it is that was all that was really available to us at that time is kind of that big pattern big fabric kind. I guess you could get solid fabrics. But if you wanted 100% cotton this is what you got. So that–that’s really different. I still like traditional patterns and I still like Trip Around the World–I don’t have any problem with that.

AM: It’s very sweet that you became the sewing authority and [AM and AH laugh.] all sewing had to go through you. I mean that’s a really sweet way that the quilt connected you with him.

AH: Right. Because it’s hard to build a relationship with a child when you’re–I don’t know, a thousand miles, seven hundred miles, whatever it is, apart. Maybe see each other once a year.

AM: Yeah.

AH: It’s hard to have a relationship or have an identity with that child. So I felt really good about that. And I hope–you know, and I hope he has fond memories of that too.

AM: Uh huh. And especially something that obviously his mom couldn’t sew. But you were the one who–that was something different that you could provide for him that she couldn’t–or she, you know, didn’t–chose not to because that was special.

AH: Right–right. So she promoted that.

AM: Uh huh. [AM and AH talk at the same time.]

[pause for 8 seconds.]

AM: You were talking about pointing out places on the quilt that were sort of crudely sewn or whatever. If someone saw this and your name was on it in a quilt show or somewhere else would you feel–would you be hesitant to show it? I mean do you have that same sense now that sort of expectations about–I mean is it okay with you if people see imperfections in your quilts now– of course they wouldn’t be like this but–because this is one of your first quilts, but–

AH: That’s a good question.

AM: How sensitive are you to, I don’t know, people’s sort of–not judging, but sort of reacting to your craftsmanship?

AH: I can’t be too sensitive because I’m not perfect. [AM and AH laugh.] I think all of my quilts are flawed and I’m not a perfectionist. So I really have to try not to be sensitive about that. And hopefully, like anything in life, you know people aren’t going to be, you know, cruel about it.

AM: Right.

AH: Openly critical. They might ‘tsk tsk’ in their head, but I think most quilters started with something like this. I’ve heard many stories from other quilters where they talk about their first or second quilt, so I don’t think it’s unusual. It’s humbling for me to look at this. To remember that, you know, that it’s been an evolution. That it’s been a journey. So I think that’s good. When I thought about which quilt to bring to the interview, you know I have one that I really like that I made a couple years ago that I hand dyed the fabric and I designed the quilt and I laid it out and I put it together and it’s got, you know, embroidery stitches on it and it’s more contemporary, but you know, what fun is that? [AH laughs.] That’s sort of incorporating what we know and do with quilts today and this is really, for me, what quilts are all about. It’s a better story I think.

AM: Yeah. It really shows that within a quilter’s life there are quilts with long stories that have long strings attached to them, and others that maybe have short stories but maybe the artistic work itself is more meaningful but the story itself isn’t.

AH: Right. I guess what I’m saying is, you know I’m just realizing this now, is that the connection we make–the human connection we make–to me with a quilt is more important than the artistic value of it. I never realized I felt that way but I think that’s what I’m saying.

AM: Yeah. So I know that you don’t have–didn’t have quiltmakers in your family, you told me that before. So you–what prompted you to seek out this–what’s your first quilt memory where you just sort of went, ‘Oh I love that, I want to do this’?

AH: Well yeah, that’s fascinating and I think about that a lot. [AH and AM laugh.] I ponder that a lot. I never had quilts in my house when I was growing up, nor can I remember any in relatives’ houses. I must have seen a quilt when I was growing up in someone’s house somewhere and it just didn’t make any impression on me. But when I was in college, so this was the early seventies, I went to visit my aunt, my mother’s sister, and I stayed with her. And in the guest room she had twin beds and she had these beautiful quilts on the twin beds. And I can remember walking into that room and really kind of being taken aback and thinking, ‘These are beautiful.’ And they were Double Wedding Ring quilts made with scraps and kind of a white muslin background. And I remember asking her about that, ‘Where did you get the quilts?’ And she said, ‘Oh I’ve had those. I got those before I got married. Those are really old.’ And I remember at the time thinking, ‘Gee, that’s funny,’ because I was in and out of my aunt’s house my whole life and she never used those quilts before. And now in this new home she was in she had put them on the guest bed. Of course I know now that in the early seventies that was the beginning of the quilt revival. So no doubt she probably–my aunt is very aware of trends and fashion, and very conscious of that. So no doubt she was aware of this and thought, ‘Oh I have some quilts. I’m going to pull them out and start using them.’ And I’m just imagining that that’s how that played out. But I do remember that as a sort of pivotal moment for me in recognizing quilts and just being really taken with it. But a funny story about that is a couple years ago I was visiting my cousin, her daughter. And we were talking about quilting because she’s dabbled a little in quilting. Now I haven’t seen my cousin in, you know, thirty years. She lives out on the west coast. And I said, ‘You know I always remember those two Double Wedding Ring quilts that your mother had on the guest beds.’ And she said, ‘Double Wedding Ring?’ And she said, ‘Well, I have the two quilts–I have those two twin-sized quilts. Let me show you. I still have them.’ And she pulled them out and they were Grandmother’s Flower Garden and they were on a light blue background. They were scraps, but totally wasn’t what I remembered. And I said, ‘Okay, was it possible she had–?’ ‘No, these were the ones she had on those beds.’ So I had sort of reinterpreted the memory as being a different traditional quilt pattern. But she still has those quilts and she is trying to figure out a way to use them because they’re a little damaged now from having been folded. They have just real–kind of bad wear spots where they were folded and [inaudible.]. I thought, ‘Isn’t that interesting how I re-imagined those quilts?’

AM: Based on what you know now about–you know–you know, patterns now, so–

AH: Yeah, because at the time I wouldn’t have known one pattern from another. So that was in the early seventies and I think it just stuck with me and whenever I would see a quilt I would be taken with it. But I didn’t know anyone who made quilts. I guess I would occasionally see them around. There was something in the town I lived in in Connecticut where their historical society, I guess once a year, would have an antique quilt sale. And they would have it in the fall and they would set up tents outside. And they would have, I guess antique dealers would come in with their quilts for sale. And I remember going to that and just being dazzled by these antique quilts. And many of them were red and white. I can remember that. It would be the fall because there would be all that sort of golden sunlight coming on these quilts. And I would just be–just really dazzled by them. And they were so expensive. You know they were thousands of dollars. [laughs.] And I just wanted to own one. I think my first–actually now that I think about it–I think my first inclination was to own a quilt. I don’t know that I first thought I wanted to make a quilt. I wanted to own a quilt. I wanted to own an antique quilt. And eventually I did buy a quilt from that antique quilt sale. But it was, you know, the one I could afford so it was, you know, like a 1930’s quilt. [AM and AH laugh.] It was, you know, $300 or something at that time. But I felt it was affordable. I didn’t like it nearly as much as any of the others. But it’s a scrap quilt and I still have it. I don’t use it but I still have it. So I was taken with looking at quilts and wanting to own a quilt. And then I guess, eventually, when I learned you could make a quilt in a day, [AM laughs.] I thought, ‘Well, that might fit into my lifestyle.’ [laughs.] So I started quilting. So I made my first quilt I think in 1987 or 1988. And until I moved to Asheville in 2005–Asheville, North Carolina–from Connecticut, I never knew another quilter. I taught myself how to quilt. I read books about quilting. We didn’t have a quilt shop. I got quilt catalogs. So it was just kind of a solitary hobby for me.

AM: Yeah.

AH: And I made, you know, I made myself a couple of queen-sized quilts. And it would take me a year and a half maybe to make a quilt. Because I would hand piece it and then I would hand quilt it. And I didn’t know that there was any reason to want to do it any faster than that. I was working so you know if I did an hour in the evening–an hour of quilting–that was a lot. So it would take me a year or more to make a quilt. But it just was always something I would have in the basket to work on. And I made a lot of baby quilts. Everyone I knew who had a baby got a baby quilt. I made myself a couple quilts. And I started–was starting to dabble a little bit in wall hangings or table runners, those kind of things.

AM: So at what point then did you start meeting with quilting groups or quilting friends?

AH: When I moved to Asheville, North Carolina–we moved here, I don’t know, I think it was on July 20th or something–and the Asheville Quilt Show was on August–whatever, the first week in August. And we went over to The North Carolina Arboretum where they held the quilt show. And I had never been to a quilt show before. And my husband and I went over there and I was blown away by the number of quilts and the variety of quilting styles. And they had information about joining the Asheville Quilt Guild. And I thought, ‘Oh.’ Because we had retired and we moved here so now I had lots of time. And I thought, ‘Well, I’m going to, you know– quilting is one of my hobbies I’m going to join the Asheville Quilt Guild.’ So I sent in my money, my dues, and I went to the first meeting. And it was really exciting. I was new to the community. And I wasn’t quite sure–they were meeting in a church–and I wasn’t quite sure where it was and I was a little unsure of finding it. And I was driving up Haywood Road in West Asheville looking for this church and I started seeing women walking from all directions to the church–holding quilts. [laughs] And I thought, ‘Well this must be the place. And people are actually bringing quilts. They bring quilts.’ Because I wasn’t quite sure what you do in a quilt guild. I thought, ‘Okay, they’re bringing armloads of quilts. That must be it.’ So I went and they had a speaker. And they had show-and-tell. And that’s why the women were bringing the quilts. And it was just wonderful. Women got up like third graders when we had show-and-tell. [laughs.] They were all so proud of what they had done. And the other guild members were so supportive and appreciative and I think that show-and-tell was–it was sort of the missing link for me in quilting. The affirmation or the validation aspect of it–sharing with other quilters–I never knew that. It was a solitary hobby for me. Although you know I would give quilts to people as gifts and they would always be very pleased with them and appreciative but it’s different when you get up in front of a big group of quilters. But that was a wonderful experience for me. And I think a real change in the way I viewed quilting.

AM: What year was that? I don’t know if you said.

AH: 2005.

AM: So not that long ago.

AH: Right. Five years ago.

AM: Do you–so you belong to the Asheville Quilt Guild. Any other quilt groups you belong to?

AH: Yes. I belong to a bee. The South Asheville Bee. My friend Ann and I started that bee– maybe two or three years ago. And we meet at Earth Fare Supermarket in South Asheville in their community room. And we meet twice a month on a Thursday morning. So that’s been really great because it’s a small group. There’s you know eight or ten of us. Usually about eight people come into the meetings. So that’s been really nice.

AM: So do you all–I guess you can only speak for yourself–but do you consider yourself an art quilter ever?

[2 second pause.]

AM: You do?

AH: Yes.

AM: You do. Okay.

AH: I do make art quilts. I do. I probably have made just about every kind of quilt. Not a quilted garment. I haven’t done that. I’m not really interested in that.

AM: What point did you consider yourself an art quilter versus a traditional quilter or hobbyist quilter? When did that change and why do you think that perception of your style changed–or your–?

AH: Well see that’s interesting because I do consider myself a hobbyist quilter. But when I say I would consider myself also an art quilter I mean because I make quilts that are meant to be hung on the wall and not used for any other purpose.

AM: Right, that’s an important distinction. You can still be a hobbyist quilter and be an art quilter. But it’s more the utility versus–

AH: I think for me in setting out to make something that’s purely–enjoyed purely through viewing it. Bed quilts–you know, you want it to be soft and you want it to be more tactile.

AM: I think that’s a factor.

AH: I think that the terminology is confusing for me, I think. All the different labels we put on quilters and quilts.

AM: It is. It’s hard to–it’s hard to self-label yourself too.

AH: Yes.

AM: Because whenever the word ‘art’ is [inaudible]. I mean do you hesitate to call yourself an artist or do you consider yourself an artist and quiltmaking is your medium?

AH: I don’t know if I would say that. I’d say I’m a hobbyist and I make quilts that are used for comfort or, you know, bed quilts and I also make quilts that meant to be just viewed hung on a wall. And, you know, another distinction is, you know, are you selling quilts.

AM: Have you ever sold a quilt?

AH: I have not.

AM: Do you have any interest in doing so?

AH: I do not. [AH and AM both laugh.] I feel really uncomfortable with it. For many reasons.

AM: So when you bought the quilt–have you ever bought a quilt from someone else in the guild for instance, or–? You bought an antique quilt once, but have you, since you developed your own quiltmaking, have you bought other quilts?

[2 second pause.]

AH: I have not. No, I have not.

AM: That’s an interesting–

AH: But mostly because–not that I don’t admire other people’s quilts or want to spend money on other people’s quilts–but one of the problems is what to do with quilts. What to do with the quilts I make. So I wouldn’t know what to do with quilts that I would buy that other people would make.

AM: That leads me to the question do you have your quilts hanging on the wall in your house?

AH: I do have some. I do. I have–there’s probably a quilt in every room. But I try not to overdo it. I don’t want to have that super-quilty house. [AH and AM both laugh.] That’s why I try– that’s another reason why I don’t make quilted garments because I just don’t want to be too quilty. I have quilted tote bags and I have quilts my house and I don’t want to walk around with that quilted jacket and wear that quilty–[laughs.] I have a lot of quilted items like–I like to make small things like a camera case. I have a quilted camera case, a quilted iPod case. I just got a new computer and I’m just trying to resist making a quilted sleeve for it.

[AM laughs.]

AM: Like a computer cozy?

AH: [laughs.] A computer cozy, right. I’m trying to resist that.

AM: Well, let me ask you this. I think this is an interesting question. I want to see what your response is. What aspects of quiltmaking–let’s just sort of get into the technical stuff–do you not like?

AH: I don’t like shopping for fabric.

[AH and AM laugh.]

AM: There. She said it.

AH: I said it. I don’t know why. I don’t like shopping in general. I don’t like shopping for anything really. I don’t like shopping for clothes. I don’t like shopping for food. I don’t like shopping, really. And I’m one of those people–and one of the reasons is–is I’m one of those people that just, you know, presented with too many choices, I’m just paralyzed. So I may know that I may need five different fabrics for a quilt that are different values. And I can go into a quilt shop and I’m just paralyzed. It’s just really difficult to make that choice of fabrics.

AM: Well, what’s the part then in the process that you really like? That you enjoy the most?

AH: I really like any of the steps. And in fact I’ll say that if I’m using–if I’m going to make something using fabric I already own, and I do like to do a lot with scraps, I save scraps. I don’t have any trouble with choosing from among my scraps. I can take my bin of scraps and empty it out on a big table, spread it out, just kind of paw through it. And I really can just pick scraps, I find that much easier to do than buying fabric in the store.

AM: Wow. Very efficient.

AH: But I like any of the steps. I probably like cutting fabric the least. But once everything’s all cut and ready to be assembled, I like that. And I always think I love sewing the binding on a quilt. And I don’t know if it’s because it’s symbolic–or you know, that the quilt’s finished or if it’s just an easy task, too. I think it’s a combination of the two, just an easy task. You’re not making any decisions. You’re just throwing it on, just going around finishing.

AM: So what does your space look like for your–your quiltmaking space? Do you have a separate room or–

AH: I do. Well I share it with my husband. When we–my husband likes to paint and draw and sculpt and he’s interested in–that’s his hobby–he’s interested in a lot of art forms. So when we were looking for a house, when we moved to Asheville and we were looking for a house, we were–really had to have a large space where we could make a mess and spread everything out and not have to look at it and walk away. So our house has a basement, a finished basement, and we have a room that’s about 30 feet by 16 feet and it’s a finished space and we–he sort of uses one half with his stuff and I sort of use the other half and I have many tables, these folding sort of three foot by six foot tables. I have three of them. And I thought they would be temporary–or I thought I would put them up as needed, but they’re always up because you know they have things stacked on them or spread out on them. I have a lot of shelves and I have a design wall. I have a big bulletin board. I have cubbies, I have lots of space to put things in. And it’s almost always messy. [laughs.] And it’s okay, you know. I mean I started quilting–when I made this baby quilt for my nephew, you know, I was doing it in the living room, setting up my sewing machine and then laying it out on the floor. And then having to put it away every time. So and cutting it out on the dining room table and having to finish before dinner so we could eat. So it’s such a luxury for me just to have this space that is so much space and I never have to clean it up if I don’t want to. Although I do, I’m–from time to time you really do have to clean up and vacuum and dust and–

AM: So–so–

AH: –and put things away.

AM: So how much time do you think you spend quiltmaking a day? Do you–do you work in your studio daily?

AH: I don’t think I work daily. Per week, I’d say probably maybe eight to ten hours on average. It depends if I’m working on something. I mean there are times when I don’t have a lot going on so [inaudible]. And I also like to do a lot of handwork. I’ve gotten, you know, I started doing everything by hand, hand piecing, hand quilting. And I really resisted machine work because I never felt like it was that relaxing sitting at a machine, pushing fabric through a, you know, a motorized metal machine facing the wall, you know, where–if I could be sitting on a couch, you know, looking at the window, and, you know, just comfortable. I do more machine work now. I’ve gradually started doing more machine work. And now I’m sort of going back again and I’m doing hand quilting and embroidery. I’ve really started enjoying embroidery–you know, embellishing quilts with embroidery. And I’ve started English paper piecing, hexagons. That’s one of my latest passions. Where you–you know, you have this cardstock form and you just baste a piece of fabric around it by hand. And then whipstitch them together. So that, you know, it’s [inaudible] work.

AM: Are there any technological advances in the last, you know, since you’ve been quilting, that have really changed your work?

[pause for 3 seconds.]

AH: Well, I guess rotary cutters would be called a technology, right?

AM: Sure.

AH: When I first started quilting I used scissors to cut fabric. And then at one point, actually someone I knew gave me a rotary cutter and a plastic ruler, and I thought, ‘Wow, this is great. You know, it’s like a pizza cutter. I can really cut a lot of fabric.’ And I thought, ‘Although where am I going to cut this fabric? I can’t use this rotary cutter on my dining room table.’ You know they hadn’t given me a mat. But I sort of instinctively knew you probably needed a mat or something. So rotary cutting really changed how I do things. Now when I moved to Asheville and joined the quilt guild and started, you know, doing more quilting and was exposed to more different techniques I realized that my 25-year old Singer sewing machine couldn’t do all the things that sewing machines can do today. I was shocked. I thought, you know, you got a sewing machine and you have it for life. You know I had–I had sewn–my mother taught us to sew, my sister and I, when we were adolescents I guess, and we would sew a lot of our clothes. And she had a sewing machine that we used. And then when I was in my early- or mid-20s my parents bought me my own sewing machine. It was a Singer. And I thought, ‘Boy, I’ve got that the rest of my life.’ I mean it was built to last. I mean it still works but when I wanted to try free motion quilting I couldn’t figure out any way to drop the feed dogs so that was a motivation to get a new sewing machine. Although later I found out because I didn’t have a manual for that Singer either, that was long gone. Later I found out though that there was a plate you could put over the feed dogs so I could’ve used it. But there’s a lot of features in sewing machines that are just handy to have. The electronic kind of things. The needle up, the needle down. You know all those kinds of things. The needle threading, and so–I don’t think they’re necessary but they’re kind of nice to have. I haven’t really done anything with computer like EQ (Electric Quilt, quilt design software.) The computer programs.

AM: Electric Quilt.

AH: Right. But I know a lot of people use that. So yeah, I think it’s–it’s moving along. Quilting is a huge business. So people, entrepreneurs all over the world, have their thinking caps on and they’re always trying to come up with the next big thing, which I sort of try to resist. I mean that’s my nature, I guess, to try to resist every new gadget. But I think many of them do have merit. So, but you know, they’ll stick around if they do.

AM: Yeah. It’s just fun to see. As you said, people are always thinking about it, quiltmakers are always thinking about it. So it’s really cool to see good things as they develop. I think it was interesting that you came to–you were talking about how, you know, what makes a good quilt to you, you know, depends on the relationship that’s made with the quilt or it has to do with the per–giving the quilt to the person. But what about–what do you think makes a good quilt just in general visually? Or do you have any sort of, do you notice anything as you’re going through a quilt show about what appeals to you visually? In terms of quilts? And can you apply that sort of as a rule or is it just something that, you know, you’ve noticed that appeals to you?

AH: I’m not sure we should apply the same criteria to bed quilts as wall hangings. Because a wall hanging–for me, I guess I would apply the same criteria I would apply to a painting or any work of art. You know, you’re going to look for composition. You’re going to look for color and original design and–

AM: Right.

AH: All those kind of things. You know, emotion. You’re going to look for that. If it evokes some emotion. But with a bed quilt, I don’t think it has to be an original design to be a good bed quilt. I love traditional designs. And they’re traditional for a reason. They stayed around for a reason. And I think, you know a lot of what’s going to make it a great quilt is how it feels. Or how it actually looks on a bed. You know sometimes you just see these bed-sized quilts and they’re hanging in the quilt show and you think, ‘That is so heavily quilted. That’s not going to hang like that. There’s no way. That’s going to sit on top of a bed like a board.’ You know, it’s not– [laughs.] So you’re sort of viewing it out of context for what it is. You know you’re not experiencing what it would be like when you’re in the bed and you’re pulling it up under your chin. Or could you even grasp that quilt, it’s so stiff? Could you grasp it in your hand?

AM: That’s an interesting point.

AH: So–yeah. So yeah, it’s just something to think–I think about when I see a quilt show. Because they’re all sort of–I mean I usually judge differently, but–

[AH and AM talk at the same time.]

AM: So whose–whose works are you drawn to? And it doesn’t just have to be a quiltmaker. Are there any specific artists or styles of art that really appeal to you or types of quiltmaking that appeal to you?

AH: I like all types of quilts. At the moment, I’m a huge fan of Laura Wasilowski.

[AM laughs. AH laughs.]

AH: I love her quilts and it’s really–I’ve made probably five or six quilts using her technique. And it’s, you know, it’s been a big change for me because I never really got fusing before and her quilts are all fused. But her explanation is, you know, for a wall hanging, it just has to hang there. It doesn’t have to be washed, it doesn’t have to be handled. Fusing is fine. And her technique is just so simple and inviting. It’s not exclusive. You know it’s not like, ‘Oh, this is how I make my quilts but you could never do that.’ It’s more like, ‘This is how I make my quilts and I encourage you to do the same. You can do just as well.’ It’s an improvisational style, which I really enjoy. I like the idea of just picking up a piece of fabric with that fusible web already on it and just a pair of scissors and just cutting shapes. I enjoy that. And of course she does both machine quilting and hand embroidery. But I really like embellishing with embroidery. But I think her quilts are just dynamic and I love doing them. And you know I have five or six and I have no idea what I will ever do with them because I–no place to hang them, and they’re wall hangings.

AM: Well, that kind of brings me to another follow-up, which is do you give–do you still give– do you still give quilts as gifts? Even in addition to baby quilts, do you give any of your art quilts as gifts?

AH: I know I’ve never given an art quilt as a gift I don’t think. I guess I would feel almost shy about that. I guess it would be harder for me than a bed quilt.

AM: It’s a little trickier.

AH: It’s a little trickier, isn’t it? I was at my sister’s house last weekend, and she had a fleece throw in her living room. And I said, ‘Betsy, why do you have a fleece throw?’ And she said, ‘Well no one ever made me a lap quilt.’ So I think I have an assignment.

AM: That is so funny.

[AH laughs.]

AM: You never should have commented about the fleece throw.

AH: But that’s the way I think about it. Why would you have a fleece throw when you can have a quilt?

AM: I just have a couple more questions. And one I was curious about whether–we live in the mountains, the beautiful Blue Ridge Mountains and we live in a community that’s very arts-oriented and supportive and there are a lot of other things we could say about this community– do you feel like your quilts are reflective of the community you live in or the geography you live in?

AH: Not–

AM: Does that ever come into play?

AH: Not the geography, necessarily, but I think the fact that we have a very vibrant and active quilt guild here so I’m exposed to a lot of quilting talent in my quilt guild. And my quilt guild brings in a lot of teachers from all over so, in that sense, that I’m exposed to many, many new techniques and ideas.

AM: We’re resuming on the second side of the tape. So have you ever pondered–one last question–do you ponder the role of quiltmaking in our culture as you participate in it yourself? I mean do you think about yourself in this time and space as a part of the history of quilting? And how that history relates to other parts of our culture or is it just something you do and you don’t think about that bigger picture?

AH: I think about it a lot. But I don’t know that I have a conclusion. [AH and AM both laugh.] I mean yes, I think quilting is huge in this country and maybe worldwide. I guess. And whether that’s just going to–when, you know, 200 years from now when people look back is that just going to be a blip or is that going to continue to grow–I don’t know, I don’t know what it all means. But I really find it fascinating to think about. That so many people spend so much of their time and energy and emotion and money on quilting. I don’t know why. I don’t know what the answer is. But I do–I do acknowledge it, and I do think about it.

AM: It is fascinating to think about that it could be a blip. Hopefully it won’t be, but yeah, that you’re part of something that might all be remembered as a curiosity or an oddity. But you know I guess we all get the sense that it won’t be, that there’ll always be a reason to or a motivation to do it.

AH: Right. But you know someone may be reading this interview in 200 years and saying, ‘Oh, this is when women did that thing called quilting.’

AM: Right.

[AH and AM both laugh.]

AH: I heard about this.

AM: Well, on that note, is there anything else that you’d want to add that we didn’t cover?

AH: No.

AM: Ok. Well thank you Alice, this was a wonderful interview. Quilters’ S.O.S.–Save Our Stories interview for the project of the Alliance for American Quilts. We’re concluding our interview at 11:17 am. And it’s still October 21, 2010.

[AH laughs.]