[addtoany]

“Passing on a Little Bit of Who I Am”: The Transmission of Quiltmaking to a New Generation

“Passing on a Little Bit of Who I Am”: The Transmission of Quiltmaking to a New Generation

By Christine Humphery

Despite the all too common image of a grandmother in her rocking chair by the fire making quilts, millions of Americans make quilts, teach quiltmaking, collect or sell antique and contemporary quilts, study quilts and the history of quiltmaking, or write and read about quilts in popular fiction. The 2010 Quilting in America survey found that 14% or 16.38 million American homes have at least one active quilter while the actual number of quilters is more than 21 million. Given that a mere fifty years ago quiltmaking was considered a dead or dying tradition, these numbers are astounding. Quilt scholars and historians are just beginning to scratch the surface recording this current phenomenon.[1. “Quilting in America 2010” presented by Quilters Newsletter, a Creative Crafts Group publication, in cooperation with International Quilt Market & Festival, divisions of Quilts, Inc. A few examples of scholarly articles on the contemporary quilt movement include: Margaret M. Bingham, “The Collaborative Relationship between Professional Machine Quilters and Their Customers in the Contemporary Quilt Movement, Uncoverings 2011, vol. 32, 79-102; Jane Przybysz, “Bay Area Beginnings: The American Quilt Study Group and the Twentieth-Century California Fiber Art Movement,” Uncoverings 2010, vol. 31, 205-220; and Marybeth C. Stalp, Ph.D., “Negotiating Time and Space for Serious Leisure: Quilting in the Modern U.S. Home,” Journal of Leisure Research, vol. 38, no. 1, 2006, 104-132.]

One of the questions that quilt historians began asking in the 1980s was how the craft passed from generation to generation in the first two centuries of the nation’s history. Historians have found evidence that older generations of women teaching younger generations within the family and needlework schools are among the most common ways of transmitting the craft.[2. Elaine Hedges, Pat Ferrero, and Julie Silber, Hearts and Hands: Women, Quilts, and American Society (Nashville, TN: Rutledge Hill Press, 1996); and Rozsika Parker, The Subversive Stitch: Embroidery and the Making of the Feminine (London, UK: The Women’s Press Limited, 1987).] This research then raised the question of how current quiltmakers learn to quilt and share the craft and found that they follow many paths. Pulled from the Quilters’ S.O.S. – Save Our Stories (QSOS) project interviews, the stories included in this essay represent a range of ways that makers, scholars, and enthusiasts are both learning about quilts and passing the tradition to future generations. Teaching the next generation about quilts is not only about teaching them how to make quilts. The following stories show that transmitting quiltmaking to a new generation is as much about sharing an appreciation for the objects and their roles within the culture, building relationships, and preserving the past.

“My grandmother was a quiltmaker…”

Women today are less likely to have grown up learning how to sew and quilt. Their mothers and grandmothers living in post-World War II America purchased rather than made household furnishings. When the back-to-the-land movement re-invigorated American’s interest in the handmade and celebrations of the nation’s Bicentennial inspired an interest in history, one response was through quiltmaking. For quiltmakers from the 1970s onward who had not learned to quilt from their mothers or their grandmothers, the problem was learning how to make quilt.

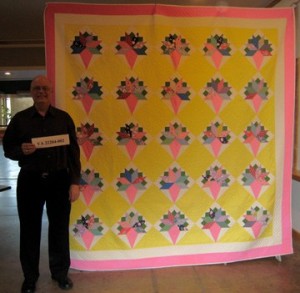

Many of the interviewees in the QSOS project had some familiarity with basic sewing skills, and often their love for quilts began with family. Fran Snay and Cliff Bailey are like many people who began quilting in the 1970s, 80s, or 90s. They referred to their familiarity with basic sewing skills or mothers, grandmothers, and aunts who had made quilts. Fran said: “It became a part of my life because when I was young, I grew up with my aunts quilting, played under the old roll down quilting frames, put a few stitches in the quilts…I was influenced by those early years in the forties and fifties.” Fran told her interviewer that she had not actually begun quilting until she was in her fifties because she had worked and raised a family. Cliff collects quilts from the 1930s and makes quilts in the 1930s styles because they remind him of the quilts he had growing up. Quiltmaking skipped a generation in his family: “So quilters in my family were of my grandmothers’ and my great aunts’ generation. And for some reason quilting skipped a generation. My mother’s and my aunt’s generation didn’t quilt.” Cliff’s grandmother and great aunt had even taught him how to sew.

Nosegay by Cliff Bailey

Although both Fran and Cliff were influenced by earlier generations, neither one became a quilter until later in adulthood. They consider themselves self-taught. Cliff learned by practice using a pattern he found in the 1970s that he liked. He already had the sewing skills, so making a quilt, he said, “wasn’t a stretch from making anything else.” Fran began with simple patterns that she slowly began to tweak. After raising a family and retiring from her career, she began quilting in 1993. Within five years she had founded a quilt guild in her hometown and started teaching quilting classes for her guild and in community education classes to encourage young quilters to continue the craft.

“I think it’s a way of passing on a little bit of who I am to my family.”

Sandra McLeod shared her love for quilting by teaching family. Sandra remembers growing up sleeping under a quilt that her grandmother had made, but her mother did not quilt. Sandra shows us that one of the most common ways to maintain a tradition is still to share it with your children and grandchildren. She is teaching her granddaughter how to quilt with the scraps from her own sewing.

Chicken Quilt by Sandra McLeod

“I have her doing little blocks, I just pick up scraps from my quilt room, and I make strips a certain width. I have her sew two together, and then a fat strip on the end…Now, her seams aren’t always straight…So, those come out. But I don’t say anything to her, I just take it out, and pretty soon I slip that to her again…I am hoping that this is teaching another generation the pleasure that I’ve had in this.”

For Sandra, quiltmaking is about sharing a meaningful experience with her granddaughter. She may take out the seams that her granddaughter sews together incorrectly, but she does not point them out to her. Teaching her granddaughter how to quilt is playing with her.

“I got started the way many, many quiltmakers get started.”

Quiltmaker and teacher Kay Sorensen came up with a new twist to the traditions of giving quilts to celebrate special family events. Her story builds upon a lifetime of quiltmaking experiences. Kay started her first quilt when she was 13, but the craft did not suit her. “The only thing I can remember is the wastebasket I threw it in.” When she was pregnant with her first child, someone gave her a quilt kit. “Having more time than money I appliquéd the quilt…at that time it was hard to find backing, batting, and so forth, so I didn’t get it finished until his birthday, his 29th birthday.”In 1999, with her skill level much greater and materials more readily available, she decided to make a special quilt for each of her eight grandchildren to celebrate the millennium.

In Living Color by Kay Sorensen

“The quilts are made for them to sleep under on New Years Eve and other special occasions. They’re not every day quilts because I want them to have them for a long time. Along with each quilt they received a journal and the journals are to record where they were, who they were with, anything they’d like to about what they’ve done when they’ve slept under the quilts.”

She knows at least one set of grandchildren always takes their quilts into the living room to sleep together on New Year’s Eve. Quiltmakers of the last forty years have been encouraged through magazines, books, lectures, and the quilt documentation projects to record what they make, the purpose for making it, and even the materials. Very few quiltmakers ask the recipients to record what was going on in their lives when they actually used the quilt. Kay’s story is a unique one.

“That’s the legacy I’d like to leave….I think teaching is probably the best thing I do, allowing other people to break that barrier that they have in their mind…”

Quiltmakers today have a plethora of options for learning how to quilt. In-person classes are available through local quilt shops, adult education programs, community centers, and quilt guilds. Since the 1980s, quiltmakers advance their skills through television shows like Georgia Bonesteel’s Lap Quilting and Fon’s and Porter’s Love of Quilting, through hundreds of books on every technique or style of quilt, and even through YouTube videos.[3.See the YouTube channel for Georgia Bonesteel’s Lap Quilting at http://www.georgiabonesteel.com/ and Fons and Porters’ Love of Quilting.] Most quiltmakers use one or more of these resources to learn how to quilt. Learning is only part of the story though. Teachers are an important aspect of quiltmaking in the contemporary quilt revival that is missing from the story of historic quiltmaking.

Diane Gaudynski and Fran Kordek provide insights into how and why they teach others to make quilts. Neither one of them mentions fame or fortune in their answers. Rather, personal contact and growth are fundamental to their teaching. For Diane teaching is part of the legacy that she wants to leave. She grew up around quilts, she knew that her grandmother quilted, but she thought it was too hard until she learned machine quilting and piecing. She is now a prize-winning machine quilter and artist with quilts in museum collections. In her teaching, one of the most rewarding aspects for her is helping her students meet their fears and realize they can be good quilters.

“…good teachers, I believe, touch people’s lives…”

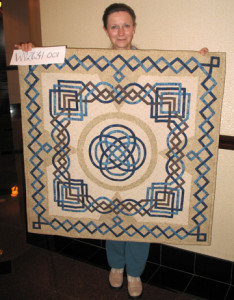

First Two, Then Four, Now Two Again by Fran Kordek

Fran Kordek approaches teaching in a similar way. Fran did not grow up with quilts and started teaching herself to quilt in about 1972. She had some sewing skills, but she found her workmanship was poor. She learned by doing or in her words: “I really believe by just jumping in and doing it, you can learn.” She began teaching a few years later at the request of a quilt shop owner. She shares in common with Diane Gaudynski the understanding that the most significant part of teaching quiltmaking is helping students see the possibilities of the craft.

“…it is not like we are going to turn the world into master quiltmakers, that is far from it, but quiltmaking is so much more than making a perfect quilt. Sometimes we feel like we should be hanging a shingle out because it gives women who are sad or grieving or have other problems a chance to get together with other women, and somebody who thinks they can’t do anything because they are not creative, when they do something they just light up and, even if it is a short time, sad women can become happy. That is very important. It sounds pretty fake but good teachers, I believe, touch people’s lives and quiltmaking touches people’s lives.”

“Each part of this project pushed us to our limits.”

Providing a place to build relationships and encourage creativity fits well into the general perception of quilts as conveying messages of support, encouragement, and love to recipients; it makes sense that teaching others to quilt also carries some of these elements. Los Hilos de la Vida, a project in southern California represents the ways in which learning and teaching a craft can help build community relationships. In 2003 and 2004, Molly Johnson Martinez was teaching parenting groups for an organization called The Even Start Project in California when she met Susan Kerr, a quilter who made quilts with artistic and social justice components. Molly had been incorporating craft projects into the parenting groups she taught for The Even Start Project as a way for women to become comfortable interacting with one another. Molly and Susan decided to teach the women how to quilt.[4. U.S. Department of Education, Even Start; “Hilos de la Vida,” Art and Remembrance.]

“I remembered my grandma talking about her quilting bees, and how the women would get together and talk about their families, and so I thought, this would be perfect, we will get the women together and they will start complaining about their kids, and we can have some teachable moments and also make some beautiful quilts. So, it backfired on me.”

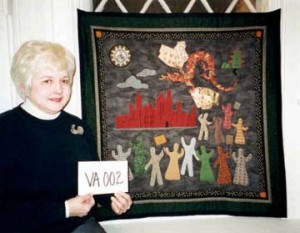

Quilt memorializing the twin towers and September 11, 2001 by Maria Ramirez

The women were learning to quilt with so much concentration that they were not talking to one another. Maria Ramirez explains: “I never imag[in]ed that it would be like this. Put your mind to work. I can do some interesting stuff because everybody puts their mind into it, everybody in class. Everybody is very interesting.” Over time they had made enough quilts to put together a show. Los Hilos de la Vida formed out of this group’s participation in The Even Start Project. Molly worked with the women to write their stories about the quilts to fulfill the literacy component of the program. During her interview in 2007, Molly comments: “Los hilos [sic] just had its second year birthday, and we have made incredible progress in those two years, artistically, with confidence, with helping the quilters overcome depression, within the community, just building community between the women.” The group grew to about 50 people.

Paola Sanchez and her first quilt

The impact of the project went beyond earning money from the sale of their work. The women also learned about their own creative abilities and gained confidence in their work. Some of the women taught their children, both boys and girls, how to quilt. Paola Sanchez learned to quilt when she was five. Her mom taught her after learning in the classes. Paola who was seven when she was interviewed already had ideas in mind for a few more quilts. She plans to make 100 quilts to sell and another 100 for herself. Paola liked earning money from her first quilt, but she talked more about her design ideas—the colors and images—much like the adult women did during their interviews. Molly touches on the creative impact when she says, “Well, it is really great because number one most people didn’t think they were artists, so seeing your mom who didn’t think she was an artist hanging, you know, her stuff hanging on the wall and people ogling over it.”

Molly was surprised by the impact on the women’s relationships to each other. In the making of a documentary about the project, Molly says women reiterated that quilting helped them break down the boundaries placed upon them by their culture. While they might all live in the same neighborhood in the United States, they had come from a mix of rural and urban areas, socio-economic levels, and ethnicities that had difficulty interacting with one another due to traditional attitudes and geographical distances. Learning together and teaching each other to quilt helped overcome these barriers and approach one another in other aspects of their lives.

“And I said, ‘Well there’s only one quilt magazine on the market, it’s a black and white, privately published by Leman in Denver.’”

As we can see through the preceding stories, learning and teaching the practical craft of quiltmaking are essential components of the transmission of the craft. Interviewees in the QSOS project mention that they learned from particular teachers or by reading how-to books. Many also mention the magazines that they read. Quilt magazines like Ladies’ Circle Patchwork Quilts and Quilters Newsletter Magazine (established 1969) and their editors have had significant impacts on the lives of quiltmakers over the decades. Not only do they present readers with patterns, they serve as documentary evidence of the quilt revival, its development and history, the significant people, companies, and events. Carter Houck shared her experiences as editor of Ladies’ Circle Patchwork Quilts in her QSOS interview.

Quilt from the 1930s remade by Carter Houck

She explains that her background is in fashion and pattern making. After graduating from Virginia Commonwealth University, she worked as a pattern maker for Butterick. Then, she and her young family lived in Dallas, Texas, for a few years where she wrote a sewing column for the Star Telegram for two years. Upon moving back East, she worked on the magazine Ladies Circle Needlework writing about sewing, embroidery, and needlework generally. Around 1974, her superiors asked her what she knew about quilting; Quilter’s Newsletter Magazine, published in black-and-white, was the only quilt magazine available at the time. She and her photographer, Myron Miller, recognized that a competitive quilt magazine needed color images. For the next twenty years, Carter edited Ladies’ Circle Patchwork Quiltssharing a love of quilts and quilt history with the new generations of makers.

Although she does not discuss her history as a quiltmaker, she claims that she is not much of a quilter. Since the mid-1970s, her reputation as editor of the magazine turned her into an author of books on quiltmaking, a respected judge for quilt shows and competitions, and an expert on quilts. “I mean I did it for twenty years… That’s the only reason I’m any sort of an expert on quilts. If you handle them and look at them and photograph them and look up the names and history of them you learn a lot. Has nothing to do with me being a great quilter.”

“…at least we’ve managed to save some of them and prevent them from going out of state being sold to dealers and whatever.”

The preservation of quilts and information about quiltmakers and quiltmaking practices has influenced the way Americans interact with their quilts. Some of the stories Carter Houck tells in her interview include visiting museums to photograph their quilts. She regrets that her team occasionally had difficulty gaining access to them in order to share images and information about them. In many ways, however, this is a direct result of the way that Americans have been taught to preserve the history of their families, communities, and states. In their quest for information on the history of quilts, enthusiasts and scholars push quiltmakers and family members to label their quilts. By 2013, groups in most states conducted countywide or statewide quilt documentation projects.[5. Many of them have made part or all of the information documented available through publications or through The Quilt Index. Books and Old Lace, a book store in Ashland, Oregon, maintains a bibliography of the publications from the quilt documentation project books.] A primary mission of the quilt documentation projects was teaching the public, collectors, and museums proper quilt care and preservation techniques. More than twenty quilt, textile or fiber museums have opened across the country beginning in 1977 with the San Jose Museum of Quilts and Textiles. The most recent ones, the Texas Quilt Museum and Southeastern Quilt & Textile Museum opened in 2011 and 2012 respectively. The goals of these museums center around encouraging good preservation practices and an appreciation of quilts among current and future generations of visitors. Through exhibitions, lectures, classes, internships, and access to their collections, museum staffs encourage the transmission of both the history and practice of quiltmaking to new generations of makers.

Joan Knight’s interview with QSOS illustrates first-hand how one of these museums came about. Joan’s grandmother inspired her to quilt, but she was also motivated because she enjoyed learning the crafts that she read about in her history books as a child. She helped cut pattern pieces for her grandmother, but she did not start quilting until she learned how to quilt from a lady at church in 1982 as an adult. By 1986, Joan owned a small quilt shop out of her home and taught classes. She joined the Virginia Quilt Research Project during the same year. As a director of the project, she spent three and a half years traveling Virginia, documenting the quilts brought to the project, and listening to the stories of the owners. “We ran into so many families that didn’t have anyone to leave their quilts to, and it was sad because they had beautiful quilts…” Out of this concern, Joan and Suzi Williams of the Belle Grove Plantation in Middletown, Virginia hatched the idea for a new quilt museum. The Virginia Quilt Museum found a permanent home in Harrisonburg, Virginia, with Joan Knight as the director when the doors opened in 1995.

Quilt by Joan Knight depicting the protests against the Smithsonian Institution’s licensing of Chinese factories to reproduce American quilts

For Joan, there are both practical sides and educational sides to encouraging quilting as a craft. At the museum, there are lectures and classes on quilt preservation and quilt care in addition to exhibits on contemporary and historical quiltmaking traditions. Since the museum cannot accept all the quilts offered, she knows that preserving the tradition required the next generations understand how to preserve the quilts they already own. “We try to help every single person that comes in, you know ‘hands on’ to show them how to take care of their quilt. And it’s amazing how they gain a whole new appreciation.” The museum offers internships to students from nearby James Madison University. She was a little surprised at what she had to teach them. “I had five grad students, and none of them had every [sic] sewed. They really literally did not know how to thread a needle or how to put a knot in the end of the thread.” While she may not have created quilters, she taught them the basics and asked them to sew educational pieces for elementary students. When asked about encouraging new quiltmakers, Joan says, “A lot of the classes come here, sociology classes and all, studying the quilts and the women, their stories, and they are really interested in the quilts after they get into reading and learning about them.” None of them, she says, know how to sew so most of the students’ questions center on how to make quilts. She hoped to offer a basic sewing class at the museum.

Joan’s story demonstrates the complexity of craft transmission from one generation to another. Did Joan ever think that learning to quilt in 1982 would lead her to being the executive director of a quilt museum? Her story and the others included in this essay show that teaching a new generation about quiltmaking includes passing on both the history and meaning of the craft as well as needlework skills. The methods for sharing and teaching a craft to a new generation are easy to categorize and are important to document. Each of the 21.3 million quilters in America could share their stories about learning or teaching quiltmaking, and we could make a list. Current quiltmakers learn to quilt in classes, from books, television, or the internet. They learn to quilt from friends, family members, and professional teachers. They might learn through adult education programs, at a guild, at the local quilt shop, or at church. This kind of list, however, does not fully explain how or why a craft passes from one generation to another.

The stories related in this essay are more than simply about teaching a new generation how to sew a straight seam or put on a binding. These stories connect to personal elements of the storyteller’s life, and through them we can see the ways in which making quilts and sharing quilts are about more than making a wall hanging or bedcovering. When people learn to quilt, they also learn about creativity and design. They may be connecting with memories of their childhood like Fran Snay and Cliff Bailey. Quiltmakers share the importance of family and community by building relationships with those around them through quilts. Perhaps, like Carter Houk and Joan Knight, they build a career out of quilts by recognizing the importance of sharing them through magazines and institutions. Transmitting quiltmaking is, as Sandra McLeod said, “passing on a little bit of who I am.”

References

2014 Ardis James QSOS Scholars

Barbara Brackman, quilt historian, curator and teacher. Barbara is the author of a number of books about quiltmaking and quilt history including the Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns and Clues in the Calico: A Guide to Identifying and Dating Antique Quilts and was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame in 2001.

Barbara Brackman, quilt historian, curator and teacher. Barbara is the author of a number of books about quiltmaking and quilt history including the Encyclopedia of Pieced Quilt Patterns and Clues in the Calico: A Guide to Identifying and Dating Antique Quilts and was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame in 2001.

View Barbara’s project: Tradition and Aesthetics in QSOS Interviews

Christine Humphrey earned her doctorate and master’s degree from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where she specialized in textile history with a quilt studies emphasis. Her scholarship has focused on the roots of American quilt documentation projects from 1980-1989.

Christine Humphrey earned her doctorate and master’s degree from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where she specialized in textile history with a quilt studies emphasis. Her scholarship has focused on the roots of American quilt documentation projects from 1980-1989.

View Christine’s project: “Passing on a Little Bit of Who I Am”: The Transmission of Quiltmaking to a New Generation

Merikay Waldvogel, author, quilt historian and lecturer. Merikay has written several books about quilts in the 20th century, including Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression and, with Bets Ramsey, Quilts of Tennessee: Images of Domestic Life Prior to 1930. She was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame in 2009.

Merikay Waldvogel, author, quilt historian and lecturer. Merikay has written several books about quilts in the 20th century, including Soft Covers for Hard Times: Quiltmaking and the Great Depression and, with Bets Ramsey, Quilts of Tennessee: Images of Domestic Life Prior to 1930. She was inducted into the Quilters Hall of Fame in 2009.

View Merikay’s project: Memories of the Late 20th Century Quilt Scene: Linda Claussen’s QSOS Interview