Bernard Herman (BH): We’re with Jean Ray Laury we’re at the Quilters’ Save Our Stories Project. We’re in Houston, Texas and today is November the third 2000 and it’s about 12:30 in the afternoon.

Bernard Herman (BH): We’re with Jean Ray Laury we’re at the Quilters’ Save Our Stories Project. We’re in Houston, Texas and today is November the third 2000 and it’s about 12:30 in the afternoon.

Jean Ray Laury (JRL): Okay, I haven’t remembered what I should start with, what I should do.

BH: All right, well I have lots of questions after yesterday’s discussion which I thought was just wonderful. And I wanted to start with your writing, is there one of your works that you particularly like above the others?

JRL: Yes, probably “The Creative Woman’s Getting it All Together” book because of the way it seems to have given a lot of women the permission to do things and encourage them to value their own time and their own needs. I guess, basically because of the feedback that came from it.

BH: What kind of feedback did you get?

JRL: Oh, people say it changed their lives and I know that’s an exaggeration but nevertheless they feel that way and obviously they were looking for something and that came along at the right time.

BH: Is there anybody in there, who responded that way, whose work has gone on to be well known in the world of quilts?

JRL: Well actually, yes, there were many well known quiltmakers in there but when I started I was trying to identify women who already valued their time enough so I knew them as crafts women and quilters and so in a sense many of them had already made that choice. So yes, most of them just stayed in it.

BH: Well, I’ve read the book and really liked it.

JRL: I have to tell you one man wrote me and said that it was time for me to write “The Son of the Creative Woman,” that would get it all together; that he had found it helpful. I was surprised too. A quiltmaker, who’s an MD, told me one time how it was helpful to him and I said, ‘Really, I had thought men found it easier to set these priorities or to consider their own work valid and important.’ And he said, ‘Oh no, I come home on the weekend and I feel like I have to mow the lawn and clean the garage. And I read that and went home and worked on my quilts starting Saturday morning.’ So that was a surprise.

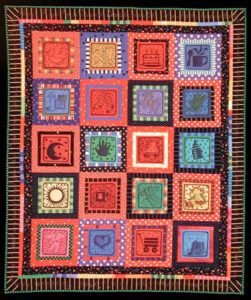

BH: One thing that we do here is ask folks to bring a quilt which you didn’t bring but that’s fine because you brought photographs which are just as good. We talked about some of those yesterday but the one you didn’t talk about, and I hope you don’t mind if I bring this out, is “Nineteen.”

JRL: Not at all. That was the quilt for the Oklahoma bombing Memorial show and I was one of the nineteen quilters invited to make a quilt that then traveled commemorating the date of that event. It was interesting working on it. I wanted to do something that picked up those little things that were going to be left at home when the parents, when things went back to normal. You know, there would still be kid’s pajamas around, roller skates– and so those were the objects that I picked out. Those kinds of things that were going to be emotionally wrenching for adults in remembering the kids and I wanted it to be high spirited and I wanted it to capture the spirit of kids. When I started the first one, I got halfway done and it was way too dark, way too heavy so I went back and started changing the blocks, getting them brighter. And this was the third aspect, when it finally got bright enough that I thought it had some of the spirit of childhood in it.

BH: It’s still somber I think.

JRL: When I look at it here, I think–well yeah, but it was so heavy when I started.

BH: Did the patterns for the blocks remain the same in design or did they evolve?

JRL: No, they’ve pretty much remained. You know, I wanted to use the pajamas, the bottle and then–I kept picturing those adults finding stuff, you know, in the home. And so I was going to use those and then I did quilt the names of all nineteen children into the border. It hardly shows, but they’re all there. They’re spelled out in long hand.

BH: This raises a question in format this seems similar to your use of panels, in other narrative quilts. I’d like you to talk a little about that on a couple of levels. First of all, how has the use of the quilt as a medium for that kind of messages that often bear words? How has that been received?

JRL: Oh, well my work is never particularly well received. I think many people see humor as something trivial. You know for me that’s where the real stuff lies. Somebody starts teasing you, that’s when you want to listen. When somebody comes to you with something really serious to talk about you can solve other things while they’re talking. So I see humor as a really essential part of living. But–you know, even with the Sunbonnet Sue books which I think of as really getting to the heart of the controversy of the “traditional” and the “contemporary,” I think most women probably bought the books for their children. And I think illustrations and humor things, often for many people, tend to trivialize the work so I think it is often not taken seriously and that’s okay. Some people ‘get it’ and it’s worth doing it for them.

BH: You talk about, sort of a tension between “traditional” and “contemporary.” Would you talk a little bit about that?

JRL: I think in my own work, I actually do incorporate it. This Oklahoma Quilt is pretty traditional in the way it’s set together. And maybe the only thing that is contemporary is the use of color pattern or the involving of printed things and words but I think in the quilt world in general there is a lot of suspicion between the two. The Art quilters, who have come to quiltmaking understand the process, and have a respect for it but I think many of the people who have come from a fiber background, and who are doing wonderful work, tend to dismiss much of the quilting world as being a kind of “paint-by-number” sort of thing. And some of it is. I think quiltmaking like anything else meets peoples’ needs at many different levels. And sometimes it’s a social need. They go to their groups or guilds because they want to see people and they want to have lunch together and visit and have coffee. And for others it’s a very serious pursuit. And I think it works the other way too. I think traditional quilters are very suspicious of the art world in general. Most of them– many of them never go to a gallery. I think they’re a little fearful of art and therefore, if somebody comes in from an art background and doesn’t have a quilt background, there’s an uneasiness or a suspicion that’s probably based on fear.

BH: What do you think the origins of that fear are?

JRL: Well, I think that art has in many ways become separated from a lot of real life. And yet, when some artists bring it back to real life it’s not very acceptable. You know that controversial stuff going on in England with people hauling unmade beds into galleries which I see as really an attempt to make art a part of everyday life again. Maybe it’s gone too far but that doesn’t seem to be working either. I don’t know why there is some much fear there but I think a lot of art criticism and a lot of art exhibits are very esoteric and they are not–I’m sure there are things within them that anybody could understand but many people also make no effort. They don’t go to a museum and listen to the curators talk. They go in and tend to be critical from the viewpoint of their own experience. Because everybody, has that same carload of stuff that we haul along with us and maybe quilt makers are even more so because the work they’re involved in is so traditional.

BH: I’m very struck by the ways in which the Art world, with a capital “A,”“ seems to resist quilting as well and you’re suggesting that quilters also at some level resist the Art world. What do you see as the basis for trying to bring those two worlds together?

JRL: Well I’d have to say that some of that suspicion is founded on both sides. There are good reasons why not all galleries will accept quilts because partly they may be unaware of what is going on in quilting and if they’ve grown up with quilting and they’ve seen quilts for years, it’s not seen as artistic in the sense of it being personally creative in the way that many other areas like sculpture and painting are. I think part of it is identification with women. I think it’s seen as women’s work and I think that’s really entrenched. I know when I used to do a lot of magazine design work if they wanted a quilt and they wanted something done in wood that went together I always said yes to the wood immediately and then thought about the quilt. Because I knew that the wood would pay three times as much as the quilt and that was because the woodworking was regarded as a male area. And I think that attitude has permeated many things and it’s not necessarily that men feel this way and have foisted it off on women. Many women feel that way or have accepted that attitude towards them. Just in terms of how they value their work. I think another part of it is that men are brought up or raised in such a way that they’re thinking of careers or most of them are thinking of a life’s work. Many women never do. And therefore, the big things that they do in their lives, like homemaking and child rearing are not associated with an income so they don’t tend to equate the time and energy they spend, they don’t equate that with money. And therefore, when they go off in another direction and they produce work and want to sell it, that part is difficult. And it means you’re saying, ‘I’m worth something,’ and that’s difficult for many women because they’ve not been told that. And in fact, many of them have been told the opposite for many years which is one of the reasons I really like working with groups of women.

BH: Tell me a little bit more about that?

JRL: About working with women? I will say that it’s fun to have men in classes because they’re open and energetic and the come into class when they’re outnumbered by the women ten to one. They’re secure. They’re fine so they’re always great to work with but I’ve noticed if I do a lecture and there are two hundred people in the audience and ten of them are men, fifty percent of the questions will come from the ten men. Now that’s not a criticism of the men for asking the questions. It tells me that the women defer to the men or perhaps they’re not comfortable exposing some ignorance in front of the men but the men are much more comfortable about actively pursuing whatever it is they want to know. I just see so many women who are capable and intelligent and lack the confidence to do their own work. And I think that’s the part that interests me–trying to help them.

BH: As a teacher, you’ve had an enormous impact. What I was interested in, in yesterday’s conversation, was that you expressed a desire that were you reincarnated you would come back as quilt historian?

JRL: Oh, splendid.

BH: That’s sort of interesting. I’d be interested in having you talk about that desire and also what you see as the objectives for quilt history? What should be happening in your mind?

JRL: Well, it’s mixed. I’m sort of ambiguous of it. When we did our state quilt search and I was lucky enough to get to write the text for it that meant I got to interview the people who had the quilts. I loved doing it, and hearing their stories, and what they had to say, and digging out the little historical things that related to this period or the date or an event. And it seems to me that research is–it can just take over your life, you know research in one area. And I became aware at that point that that was a direction that I could have found equally exciting and at the same time I know a friend who is a conservationist was scolding me one time about something I had done in a quilt that wasn’t going to last. And I said, ‘I can’t worry about that. I’m not interested in that.’ ‘Well,’ she said, “that’s going to disintegrate in a hundred years.’ And I said, ‘That will give you conservationists your work.” But it–and I know that’s part of preserving quilt history, so I say I’m interested in it and in another sense I don’t show that practical kind of interest in it. And I think that what that comes down to is that I’m not a great quiltmaker, and I’m not so interested in the quilts. It’s the process of quiltmaking. You know I would not want to have a quilt stolen but it wouldn’t–I wouldn’t suffer terribly if a quilt disappeared. The finished physical thing is not the main part of it for me and I know that people feel very differently about that. Most people do very highly value their quilts and maybe that’s a contradiction to what I said earlier about women valuing their work but I like what happens internally. I have probably never done a quilt that I was really satisfied with so when I’m done with one I’m sure I can do better on the next one and that didn’t please me so much that I could stop there.

BH: I like the idea of sort of the two phases of work. Work is process and work is product. People refer to some thing as this is the ‘the work’ and some people demonstrate it. One of the things that appears in the world of quilts is how deeply attached the object is attached to the narrative, the story, and if you think about becoming a quilt historian in your second life, unless you’re already in your second life, and that’s going to be your third one.

JRL: That could be, yes.

BH: How would you see recovering narrative from historic quilts, where we no longer know the maker?

JRL: I think what’s intriguing about the quilts where we don’t know the maker or the information is what we can figure out, I think that’s still what we’re looking for. When a quilt comes in that is totally anonymous, somebody bought at a garage sale and you don’t know where it came from–it’s the narrative part we still look for. We look for clues, for the date, names and outlines of buildings or anything so I think that’s really sad if that’s lost but I don’t think that the interest in it diminishes. I’m not sure if I understood your question right or if that’s it.

BH: I’m just puzzled by the problem that I see in these interviews with the quilters across the board, how deeply attached the personal stories are to these objects. And I wonder what happens in terms of the future, when that voice which goes unrecorded is gone but the object continues. How do we affect some sort of?

JRL: I suppose in a way, if we’re going to think of quiltmaking as an art form then you have to be able to separate them and still have the work on its own be valid. But certainly with painting, a painting is made more interesting when we know the painter and what was going on at the time. However, other paintings survive and we know nothing about them and it doesn’t seem to diminish our enjoyment of them visually. So I don’t know, I don’t know how to answer that. I guess they have to be both and if they’re not both there we’ll draw out what we can from the visual. I don’t think we feel compelled to do that with other things.

BH: I think you’re right and I wonder if that’s part of the package of quilts as women’s art and with attention to the art world if somehow all these things aren’t somehow linked.

JRL: I’m sure they are, yes. I hadn’t thought about it like that but, I’m thinking you’re absolutely right.

BH: Well, I want to shift gears again and talk about your magazine work in the ’50’s and I think continued in the ’60’s? JRL: Yes. BH: I can think of one other–well there are several other American artists that have had a major impact that also published in that venue–Frank Lloyd Wright did designs for Ladies’ Home Journal. [magazine.] I wondered if you would talk about that medium.

JRL: Well, one of the reasons that I got into it was because people were going to look at my work. I mean that’s pretty rewarding. And also they were very willing to pay me for it and that was important at that time. And the payment really validated me in the sense that it confirmed that it was okay to do that instead something else. In fact one of the very first jobs I ever had when my kids were little was doing the little drawings for the Pitney-Bowes machines that you put on your envelope. And they paid me like $25 or $30 per drawing; and might take like fifteen minutes to an hour and a half. And I always did those when they came by because that was the money with which I could hire household help–somebody could come in and do all of the chores, the mundane things, so that I could have more time for sewing. And there was something about not walking–you know if you walk into a kitchen and you’ve just cleaned it up and somebody has left their dirty dishes there and some food on the counter, there’s sort of a clue there that they didn’t value your work real highly because they didn’t take care of it. So if you look at it and say ‘so and so will be here tomorrow and it’s not my job,’ then you don’t hold it against that other person either. So I think in a lot of ways it made it easier to be–you know time was always a problem–but when the kids were little I think it made me much more accepting of children’s behavior because I could separate myself from that housework. And so doing those drawings really released me to pursue my own work and the magazines did pay well at that time. I don’t think they do now but it was a good job for me and I loved having them appear. You know your mother runs next door and shows the neighbor and she wasn’t running over with the quilts I did to have at home. And I think in that sense it took it out of what was ordinarily thought of as woman’s work and it was seen as more important because it was in a magazine.

BH: Although what you describe is I think classified as illustration and illustration like quiltmaking seems to often operate on the edges of the Art world in the fact that it’s creative, highly conceptual, and involves a level of abstraction which is really incredible, and yet you don’t see the same kind of discussions occasioned by the works of illustration and advertising art.

JRL: No, that’s true. I don’t know what to say about that. I agree with you. And there’s I think in the magazine work too–just another point–there were often limitations. Muted colors like violet and rust don’t photograph very well. They didn’t have photo processes that could show those colors so I would be pretty much limited in terms of what would photograph well. Besides which, when a magazine came out the magazine would get all these letters wanting to know where to go get those exact fabrics so if I used solid colors, it was pretty obvious, I used red or green, anyone could go out and find red and green. But if you used complex fabrics or printed fabrics they’re stuck because the work starts the year before the magazine comes out and a year later they won’t find the same fabrics. So those limitations, I guess, affected what you could do. And I think I personally didn’t regard those as my more serious quilts. And I think I probably did view them as illustrative material. And it was done often to fit into a room, although they usually fit the room to the quilt.

BH: Did you get feedback on your articles?

JRL: Yes, yes I was good friends of the women who were editors. One of them was Roxa Wright, I don’t know if you’re familiar with her, she was the one who started the main interest in the “Deerfield Embroideries”, she had been at House Beautiful, and then freelanced for Better Homes [and Gardens magazine.], and Woman’s Day and so on. She was a wonderful woman; she was just great and had a very interesting history. And she was the one who commissioned the first article. And then, later when she retired, I got to know Deborah Harding who was then a Woman’s Day editor, and that was fun. I was always the ‘country girl’ when I came to New York, and she loved nothing better than introducing me to things I had never heard of so we had a great relationship there. And she was good to work with in the sense that she was open and she would listen and we could talk about an idea and then she would go off in there to do whatever else was needed. Occasionally, it would start–I think I mentioned yesterday–they were going to photograph barns in October so what can we do with barns. There were a lot of possibilities and they loved the hex sign idea, so that led to a quilt with hex signs so it was always a two way thing but the ideas never came strictly from me so for me that was something I did as a job where as most of the quilts I make are not. The commissioned things might be, like for a bank wall, and I love doing that. I love doing commissions partly because they’re usually large scale and they have nice settings. And I often work with just one person – the architect or the designer. I don’t like making things for people’s homes. I’d much rather–I’m too aware of their personal tastes and what they like and I want them to just come and look at things and choose artwork. I don’t want to deal with all that. You know the expression ‘Good art don’t match the sofa.’ That’s– you get into things like that in people’s homes.

BH: When you first started out and started moving into the world of the Art quilt and the statement quilt that was really new territory and other people weren’t doing that. They were looking at quilts where they were inclined to do so as art and not the other way around. How did you come to the medium as an art form?

JRL: I think when I did my very first quilt, I felt so at home with the material and it was so comforting to find something where I could really control the shape and I never felt that control with other media. And I guess, I just didn’t think–I just didn’t know a lot about traditional quiltmaking and there weren’t quilt makers in my family so I didn’t have either the benefit or the burden of traditional ways of looking at them. So I guess it just didn’t occur to me that you couldn’t do with fabric whatever you were doing. and I always liked graphics because I liked graphic design so it just seemed like an extension of that.

BH: There’s no quilting in your family, you were largely unfamiliar what is classified as traditional quilts so how did you pick this medium?

JRL: I saw a quilt one time that had been made by a soldier during the Civil War and I can’t even tell you where it is, and I’ve tried to find it. It was in this little museum in Kansas somewhere, a little country museum on the edge of a small town and this quilt had–it was so personal. It was so wonderful and I was so moved by it. The soldier had used scraps of shirt and uniforms and whatever materials he could get and he showed the farm–his farm in Vermont and behind the farm was the pine forest and in front of the farm was the apple orchard and the lane that went by and the family. You know the stair step children and the grandparents. And it looked to me as if everything he ever cared about was in that quilt. And it just seemed like that was what a quilt ought to be. And so when I made my first quilt that is what I had in mind and that is what propelled me, I guess. What drove me to do a quilt. Remembering how simply he had accomplished this colorful, wonderful quilt. And I don’t think I’ve ever seen another quilt that was as moving as that one was. I didn’t even take a picture of it. It didn’t even occur to me that this was going to ever influence my life.

BH: One of the things Le Rowell asked me to do with you is to talk to you a bit more about where you came from, I guess growing up in the Midwest?

JRL: I grew up in a family of four girls and a somewhat autocratic father. And my mother was a teacher and was very supportive of whatever we wanted to do and helping us. And I could see a relationship between my mother and father in which he made the decisions though my mother often had the wisdom to make the decisions but the call was in his hands. And I think I saw that early on and I saw a conformity in the small town that I didn’t like. You know I don’t know how you grow up in a Republican family and get Democrat or how you know how any of these things come about. When I’m with one of my sisters we can’t talk about politics, or religion, or education, nothing that has significance in the world because we’re so far apart and we’re just a year different in age. Our bringing up was very similar and heredity is obviously the same so I don’t know how people come about looking at the world in different ways but it’s interesting. I’m very conscious of needing to be approved of and liked but there are parts of me that I can’t give up for that. And I think sometimes when I think about my sister I think she needed that approval, community or family or whatever it was. And I know I need that too, but not enough to have it interfere. You know even racial attitudes in a small town–I can remember being in third grade when a minstrel program came to town and being so offended by it and nobody understood what I was talking about and what was the matter with me that I couldn’t enjoy this good entertainment? So I suppose, maybe it was stubbornness but there was always a streak. I didn’t rebel. I was much too docile to ever rebel outwardly or physically but I think I mentioned that yesterday about not liking confrontation.

BH: Your quilts provide your medium to make the statement.

JRL: Yes, yes.

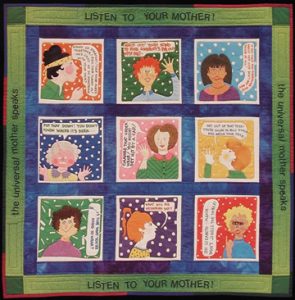

BH: It was great. If you could tell us again about one of your best known quilts of all time, which is “Barefoot and Pregnant.”

JRL: Oh, yes. That came from an obituary in our newspaper, when Senator Van Dalsom died they had a little article and they made a reference to him being called ‘the barefoot and pregnant Senator’ because of his comment in the legislature. He always claimed he had been quoted out of context. When you went back and read the whole two sentences, it was even worse. And I just thought nobody should forget who that man was and so that is what prompted it and you know having it in that cartoon format people do read it.

BH: Oh, yes.

JRL: People who would never have otherwise acknowledged the statement will read it. I mean it seems pretty prosaic now but when I did it, there were women who didn’t like it. I don’t know why. Oh, I think I do know why. I think some of them read that and thought that it was something I had said. I don’t know.

BH: That quilt was picked up and reproduced by Planned Parenthood, is that correct?

JRL: They made a poster of it as a fundraiser, yes.

BH: What did that do to your career?

JRL: Well I don’t know that it really affected it except that I really liked seeing the work being–seeing a piece of my work being incorporated in something I felt really strongly about. And some of the letters I got were wonderful. One was from a doctor in Florida, a woman. She and her husband were both MD’s and she had said that she had been fighting this battle for so long and when that poster was sent to her, suddenly she said that here was a way of dealing with it with humor. And it gave her a fresh start. And I think responses like that–you know if there is one like that it makes up for other ones. So they did have kind of a party when they had the quilt installed in their office and so I to go up for that and be heckled and poked at and that was an experience. I’m not one to go out and march in a protest, that’s not my way to protest so it put me in a situation I had never been in before and that was interesting. That didn’t really affect my career, maybe, but I enjoyed that and getting to know that group of people.

BH: Well, we’re nearing the end of our time and one of the questions on that sheet– because your work is so well known and you have had such tremendous impact on so many people is what do you think your legacy will be in terms of the quilts that you have made?

JRL: I don’t think that my legacy is going to be in the quilts. I think it’s going to be in the encouragement I give others. And I have a real good time making quilts but I don’t have illusions about the value of the pieces I’ve done. I couldn’t not do them. I have a great time doing them, and at the same time I’m always too pressed for time. They’re never as detailed as I’d like, there’s never as much quilting as I want to do. So there is always a kind of dissatisfaction when I’m through. So when you finish a piece there ought to be a sense of accomplishment and finality and real pleasure. And sometimes it’s nice. I can enjoy seeing it done but there’s never real satisfaction, because there’s–I never did quite what I had envisioned. Is that what you meant, is that what you–

BH: Absolutely. Is there anything that I forgot or misdirected?

JRL: I can’t remember what it was I thought of yesterday. There was something that was asked yesterday that I answered and then I thought later I needed to elaborate on that so if I could put that on the tape I would.

BH: Well, thank you for participating in the Quilters’ S.O.S. and I look forward to continuing these conversations in the future.

JRL: You’re very welcome and I’ll look forward to that too.