Karen Musgrave (KM): This is Karen Musgrave. It is August 29, 2001. It’s 5:09 in the afternoon. I’m conducting an interview with Juanita Yeager for Quilters’ S.O.S. – Save Our Stories project in Louisville, Kentucky. Juanita, tell me about the quilt you brought in today.

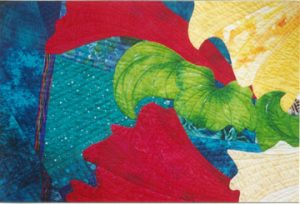

Juanita Yeager (JY): This is called “Red and Yellow Number Two.” Although I have someone who thought it should be called “Rooty Tooty.” But it’s the second in a series of quilts where I have used this particular floral design, the big flowers. It’s what I call flowers on a grand scale. I’m currently into a series of doing those kinds of flowers sort of ala Georgia O’Keefe but not necessarily totally as she painted them. But this one is two big flowers. I love flowers. I love color. And the reason I do my quilts mostly is for the color too. I use flowers as a transport or a vehicle to convey color. And so these flowers–while I love flowers. I love organic shapes. I’m not a gardener. I don’t do dirt. I’m just as happy to go to a nursery and buy my flowers and bring them home or bring cut flowers home to the house where I usually always have them in the house. And so my flowers have the shape and suggestion of a particular plant, a blossom but they are not botanically correct. I don’t–I’m not trying to illustrate or be an illustrator of a particular flower in cloth. And so when I go about doing a quilt I usually have a focal blossom and then maybe have some side views and some bud shapes and some leaves. And it’s not even necessarily the leaf that really goes with that particular flower. So once I find an interesting shape for a flower I may search for an interesting leaf shape from some other flower and generally the source of my inspiration or the source of my flowers is usually nursery and seed catalogs which a friend of mine graciously passes along to me. So that’s where I usually and get the first inspiration or I may get it from a magazine that shows a picture of a flower. You know a gardening magazine or something like that. This quilt is appliquéd–all the flowers are appliquéd and it’s on what I call a multi fabric background that is fractured.

KM: Is that typical? Do you typically fracture your backgrounds?

JY: I’ve been doing that a lot lately. I’m trying to find ways of making really interesting backgrounds for my quilts that don’t interfere with whatever the subject is because I really don’t like the idea of just putting something there for the foreground without something visually interesting in the background as well. So this quilt was probably the third or fourth a long in the series and I’m just trying different ways of fracturing, some very regular patterns and some very random.

KM: What special meaning does this quilt have for you?

JY: It’s really hard for me to say that I am emotionally attached or really have meaning to a quilt. I brought this one as an example of my work. One because it depicts the color pallet that I really like to work in but sentimentally this is really the last quilt that my husband saw that I completed before he died in January so this one has some emotional attachment for me. And he [Phillip.] was always very supportive of my work. He was actually my number one fan and promoter and he would just take me anywhere. If I needed to get to a quilt show or get my work exhibited or something like that, he was just out there always pushing me forward. He was very supportive so this one is dear to me for that particular reason and he really liked it. He would just– Let someone come to our door he’d jester them in saying, ‘You’ve got to come into Juanita’s studio and see what she has on the wall.’ He was just like that.

KM: How has your quilting impacted your family?

JY: When I first started quilting it was to save my sanity so to speak and but I think the beginning in–I started in ’83, ’84. But beginning in about ’88, I knew I was serious about quilts. My husband knew I was serious about quilts. And my children knew I was serious about quilts. My grandchildren knew I was serious about quilts. [laughs.] All of them are proud of what I do. They all love what I do. They all have their name on a list waiting in line to inherit the pieces. And to save them from killing each other when I die I have this list in my computer that as I finish each quilt it’s assigned to a child but if one of the pieces gets sold then their name gets–you know moved to the next piece–that quilt gets whited out and another one gets put in its place or something like that. But they all value what I do. All of them are proud to display them in their homes and that sort of thing. They are very supportive of me.

KM: What type of quilts do you make?

JY: I make what I call art quilts. They’re always for the wall. I have done, very early on a bed quilt. I started lots of bed quilts. I only finished one bed quilt and I think I started it probably in ’86 and finished it about ’88. It took two years back then I was working as a registered nurse full time. And I sent it off to the Kentucky State Fair for a competition for first bed quilts and it won a blue ribbon. And then I sent it to another competition where it also won a blue ribbon. Well I got a big head. [laughs.] Whoa. I know what I’m doing and I didn’t know [laughs again.] what I was doing. That particular quilt is a 1930 pattern with curved seams. It was on the cover. I think it was issue 102 or 107 of Quilter’s Newsletter Magazine. And where as before when I started in ’83 I think I started with what everybody else did in that era making quilt block quilts. Log Cabin blocks. Star blocks. I must have tried to do every star pattern I could find. I was always at the library getting books out, looking at patterns and trying them. Just samplers. Teaching myself how to put them together. But the colors of the fabrics in the early ’80’s were those dusty rose and powder blues and gray blues and beige and you know everybody’s colors–they were ugly colors. It wasn’t where I was. [KM points her finger down her throat.] Yeah. Yes. [ laughs.] And so even though I liked the feel of fabric and the tactile feel of fabric working with the fabric and liked the challenge of figuring out how to do each block. Draw them. Do my own templates because I’m math minded. Once I knew I could do it there was no longer a challenge to complete it and there certainly wasn’t a challenge to complete 30 or 40 of the same thing repetitively on and on and on and on and on. The reason I think I finished my real first quilt as I call it is because it had curved pieces. It was a lily or tulip. A 1930 stylized flower. It was pink, soft pinks, dusty rose because you couldn’t get anything else but there was a lively green and very nice yellow which makes the quilt pretty. And so consequently I was saying, ‘Well, you know for me it really is all about the color.’ And so when you think about quilts you’re really looking at color and as women I think when we think color we probably have thoughts of flowers and flower gardens and that side of things. And we think of yellow daisies and red roses. So I think flowers or doing flowers was probably that next step in doing in doing quilting and finding patterns and I do like appliqué but I found I didn’t like doing that little bitty tight teeny appliqué stuff. I definitely don’t like Baltimore Albums. [clears her throat.] It’s too fussy. So I would probably say from ’88 through maybe ’94 or ’95 when I really started thinking about flowers, a single flower, a single bloom and working on a large scale. It was really an era of trail and error and search and seek. I went through doing a series I call “Flowers in the Round” which are circle flowers divided and sectioned in original settings. The Round Flowers I could say was truly my own style at that time. One of the quilts that I did make in that series–the first one I made started that series, I really woke from a dream with the design in my head. Got up, went to the drafting table and drew it out in full size and made it and sent it off to the Hoffman Challenge. This was probably in ’91. And I was delighted they took it. [laughs.] And it traveled. And from that one which was the first flower in the round design I went on to make a second one that I called “Lilies of Autumn.” And that particular quilt–that quilt I made featuring round flowers is now in the permanent collection of the American Quilt Society in Paducah [Kentucky.] So if I have one claim to fame that’s probably it. [laughs.] That’s probably it but also before the museum purchased it I entered the quilt in a Better Homes and Gardens competition. First it was judged on the state level. It won the entry for the state of Kentucky then it went on to be judged nationally and it wound up winning the grand prize for the national competition which was truly a big head time. [laughs.] But a–so from there I’ve made probably several other quilts from that series that have been juried into and exhibited in different places and that sort of thing.

KM: So you’ve been published?

JY: I’ve been published. Not only with the quilts as a result of being in AQS [American Quilt Society.] magazine. My quilts have appeared in Quilter’s Newsletter Magazine. I’m part of the Communion of the Spirits [A Communion of the Spirits, Roland Freeman, Rutledge Hill Press, TN Nov. 1996.] quilts that Roland Freeman did when he was looking for African American quilters across the United States. I have a quilt in an AIDS Publicity Calendars, how that happened was really kind of funny. I made a quilt early, very early on which was a pineapple block that I called “Decidedly Red.” The block was constructed wrong but I put the quilt together anyway. It just made a very interesting geometric kind of abstract pattern across the surface of the quilt and I sold it in probably 1990, the first quilt I actually sold. It was to a lady who was looking for something to take home to Senegal as a memento for having been in Kentucky and she had looked at several other quilts, traditional Kentucky made quilts and didn’t find anything she really liked. I showed her this piece. It was probably 45 by 45, not a very large size but she fell in love with it; the colors I think more so than anything just a variety of reds and black and a real vivid blue that kind of wound its way across in a kind of woven pattern intergradations so she purchased it and of course I was very delighted to have sold a piece and I thought I would go buy myself something. Last year–year before I came home from teaching in Virginia to a guild over there I got this phone message when I went through my messages on my answering machine and there was a lady in New York and she said, ‘I’ve seen your quilt.’ And she said, ‘It’s called “Decidedly Red.” My next door neighbor has it.’ And she says, ‘I want to include it in a calendar.’ And she says, ‘Can I have your permission to publish it? Give me a call back.’ And so she left a number and I called her back and she told me. When I thought this quilt was in Africa. The quilt is back in the United States and was in New York. And I said, ‘Well, sure I have no problem with you using an image of the quilt.’ Because this was for the International AIDS calendar and their fundraising project. And I said, ‘Yeah, no problem.’ So she says, ‘I’m going to send you a release because we have to have your permission to publish it in writing.’ And she says, ‘And when we get the release back signed we’ll send you a check.’ And when she told me how much she was sending a check for I almost had apoplexy, you know. [laughs.] I was thinking, ‘My God, they are paying me six times more for the photograph of the quilt than I got for having sold the quilt in the first place.’ It was–and so I thought, ‘This is really neat.’ And of course as a result of that I think about last month or so they had a little blurb of the quilt on their web site and so they sent me more money. So it’s–so in that way outside the quilt community people who looked at your work as art know that there is value in the visualness of it and realize that the person who made it needs to be treated as an artist as well as anyone else who has made a photograph or sculpture or some artwork or something like that.

KM: Are their quilters in your family?

JY: No. Not a one. I didn’t know there was such an animal as quilts until I caught a blurb on Georgia Bonesteel on the television and this was somewhere in the ’80’s. And at the time she was doing this little blurb that I was probably walking from the bathroom through my bedroom and it just happened to be on the educational channel and I stopped and looked and I thought, ‘Oh God, that is ugly fabric. What is she doing?’ And went out of the room. And it probably was on enough that it just caught my attention but no, I was raised in the city in a house with central heat. My family was well off enough that we could buy our goods and so consequencely there was no need for the utilitiness of covers for warmth and that sort of thing and my mother was not a needle woman. Now my father’s mother was the only woman in my family who was and this goes back to even my maternal great grandmother who lived until I was 13 so I knew very well that she did nothing with her hands as far as needle art. My paternal grandmother tatted, embroidered and crocheted and all of that kind of handwork but she too had no need for bedcovers which was what quilts were generally used for so it just wasn’t a part of my raising to know about them. And so–but I think probably when I got into quiltmaking it was with the understanding that quilts were quilts and quilts were to be used as bedcovers but once I got through that first one which took me two years to do I began to rethink quilts. Nobody has slept underneath my first quilt. I made it initially thinking that I would make it for my oldest daughter and then I would make my other three children quilts and they don’t have bed quilts to this day and neither does she have that one. [laughs.] It’s–I still have it at home. It’s folded up and it’s in a basket as decorative thing. It’s not being used at all. [laughs.]

KM: So what age did you start quilting?

JY: Oh, you’re asking age.

KM: That’s all right.

JY: I’ll tell you. Let’s see. I started in about ’83. [KM: quietly ‘Okay.’] So I was into my forties, yes. I can’t believe it. [laughs.]

KM: Have you ever used quilting to get through a difficult time?

JY: Yes. I do. Quilts–if you look at–there was a period—I had a really bad period probably ’94 through ’95 but I never lost the desire to quilt but what I did notice was that my color pallet changed drastically. I was doing everything in black and gray and awful depressing colors because that was my mood. I mean I was in this funk of a funk of a funk but anyway I kept quilting because it kept me sane. Disbelievingly everything I did during that period people liked they wanted. I would start a piece and someone else would be willing to finish it. Then I would start another dark depressing piece and couldn’t keep on with that particular piece and somebody would take it off my hands and finish it. You know, because they did like the color. The colors didn’t represent their mood just mine. And finally probably January of ’96, I climbed out of the dumps as I was finishing a piece that I call “East of Morning,” which is an original design. It got me back into using curves again and it has a big sun face on it. It’s very bright. It represented hope and I could see light at the end of the dark tunnel that I was in. The background was basically dark purples but it was no longer black. And the–I used Mariner’s Compasses in the composition of the piece Mariner’s Compass in place of stars. The compass stars were done in bright colors so I knew that I was coming out of my dark place at that time. This year even though my husband–last year–no this year last year even though my husband was diagnosed with a terminal cancer through all of that I still kept quilting and I kept working in my color pallet and that I think I have to attribute to him [Phillip.] because of the way he accepted what he had and he would not let me get into a funk. You know, he said, ‘It’s nothing I did to myself and you have to go on. You have to do what you do.’ So that’s why my “Red and Yellow Number Two” is a bright, cheery quilting and so everything after that has been as well.

KM: What are your plans for quilting in the future?

JY: I’m going to keep on keeping on. [laughs.] I am now exploring I think more seriously because I think I have kind of solved the problem, which for a while I was trying to do with several quilts, was trying to solve the problem of working with flowers that looked real enough without overly augmenting them with other mediums like paint. That one does have some fabric paint to give some depth to the flowers and it does have some thread work on it. But I didn’t want to stretch as far as actually painting, you know, using acrylic paint but I will use fabric markers and maybe some diluted dyes because I think dyes, inks don’t change the hand of the fabric. I didn’t really want to change the hand of the fabric because I still think quilts even though they’re for the wall still have this tactical snugness, the feeling of comfort that I want to preserve. I don’t really want my work to feel like I’ve got a stiff canvas even though it is three layers. So I think I have pretty much solved what I want to do with the flower part of it. I think now I’m looking more at what I can do to enhance the background. So my current piece is also a flower but I’ve now fractured it with curved lines in a grid and that sort of thing so I guess it is a step beyond this piece.

KM: Is this hand appliquéd?

JY: This is hand appliquéd. Most of what I do is hand. I loved handwork. I do have a near top of the line sewing machine but I absolutely hate [laughs.] machine work and so I’ve said and not in talking about people and what they do. I will say I will do everything except straight lines by hand, you know the kind of idiot work you know, sew a straight seam then I will sew it on a sewing machine but for more intricate things I find I have no problem I am really a fast hand piecer. And love hand quilting. Most of my pieces are hand quilted. My bigger pieces I quilt in a floor frame. This particular piece I was on deadline a little bit too tight one. I sent it as an unfinished in progress piece for consideration for an exhibit at The Kentucky Museum in Bowling Green, at Western Kentucky University along with a couple other pieces for consideration that were completed. Of course naturally that’s how it usually goes, they want the piece that is still in progress and the deadline was looming so I had to quickly do something with it so the flowers are machine quilted and the leaves too but when I got that part done and I knew I was not going to be happy with it unless I did the background with hand quilting so it’s a combination of both.

KM: How do you feel about long arm quilting?

JY: No. I’m saying no because I really have not found the love for any sewing machine. And I think you have to love your tools and I think you have to be at one with your tools. And I’m not at one with my sewing machine and I don’t think I can make myself that-into that. I think it would be totally–it’s totally foreign to me to do that. I have found people who master it. It’s like anything else. You know, it’s what you master. It’s what you love. And if you can–if the end product is ecstatically pleasing, visually pleasing and well done no matter what tool another artist chooses to use then I’m fine with the end result. How they achieved it but for me to do my quilting that particular way, no I wouldn’t.

KM: From whom did you learn to quilt?

JY: Essentially I taught myself. I started off with a pattern once I did decide to try it, ‘Oh well this looks a little interesting,’ and went off to buy fabric and came back from–with a little Workbasket Magazine with a pattern in it. I didn’t know you needed template plastic. I was doing the pattern similar to what you would do as a dressmaker. You know, thin pieces of paper pinned onto the fabric and cut around with a 5/8-seam allowances was how some of the first things that I put together that’s how they were constructed then I went off to library and started reading books and they said, ‘No quarter inch seam allowance is what you use and you use plastic.’ And then I discovered quilt shops as oppose to the fabric stores and then probably by the time I finished the second–the quilt that I consider my first quilt then I thought well maybe I need to go take some lessons from somebody. I mean I had won these blue ribbons but I didn’t think I was truly deserving of them. And so I went off to take a class from the Jefferson County Adult Education Program and the teacher there didn’t teach me anymore than I already knew. What she did was provide some vital information to me at the time. Although I was grateful to her for she did tell me about quilting guild and the local Nimble Thimbles Guild which I did not know existed. She told me when and where they met and she also told me about AQS [American Quilter’s Society.] So I am one of the original charter members of AQS, which I think was probably in ’88 because their first show was in ’88. And I did go to their first–I think I went to their first show in ’88. I know I was there in ’89 and saw what quilts were and course, then it was just a whole other world besides what I saw in books because most of the books were older books. They were from around the time when the quilts came back into being in ’76. And I read magazines and I saw there were– you know, what people were saying were quilts in ’76 but they were all bicentennial red, white and blue kind of things which were kind of–it wasn’t in my color pallet and I wasn’t going to decorate a room in that way so The Ladies Home Journal look just sort of passed me by, you know. It held no interest to me so–but when I went off to see the quilt show I thought, ‘Wow.’ You know it’s like one quilt was much more breathtaking than the next one although they were bed quilts then I went downstairs to the wall quilts and it was just another world. It was just phenomenal but I didn’t know that I could do that in ’89. And I knew that I could probably take some traditional patterns and modify them somewhat and work in a smaller size not just for the bed but for the wall. And I did a lot of contest competitions and stuff like that early on. You know entering NQA [National Quilt Association.] contests and those kind of things and challenges and fabric challenges. I think I probably had a more traditional route to where I am then most people who went toward art from early in the ’80s and currently.

KM: Do you teach quilting?

JY: I teach quilting. I teach beginning quilting if I have to. I really much prefer to teach people how to find their own style, how to make what’s in their head, what they see, what they can visualize and of course I tell them that if they can draw, if there is someway for them to get it out of their head as a line drawing on paper then I can teach them the techniques they need to get it from that line drawing into fabric. And so I really try to stay abreast of what is new technique wise- foundation piecing, freezer paper, the use of this and that, raw edge, etc. And actually I do teach machine quilting which astounds some people I know because, ‘You teach machine quilting and you can’t stand it.’ I say, ‘Well it’s easy to teach a technique. You don’t have to love it to be able to teach it.’ I don’t think as long as you understand the principals of it.

KM: Where do you teach?

JY: I teach locally. I teach at the Artopia which is what the facility used as studio and gallery space by the Louisville Visual Art Association calls it. I’ve taught through the University of Louisville in adult continuing education program. I taught for a time through the Jefferson County Adult Education Program. I have classes–I have ladies who come to my home to take classes. Right now I have two groups–two days of ladies that come. There’s a group that comes on Monday nights and ladies that come on Tuesday nights. A lot of people know me across the country so they will call me and say, ‘Can you come over and teach?’

KM: What do you like about teaching?

JY: I like sharing what I know with people and I love the enthusiasm a new quilter who has just found it has. [laughs.] Sunday I had a group of five ladies at the house who were dyeing fabric and I thought it was going to be an hour introduction on hand dyeing and it turned into this miracle of , ‘Can we buy more fabric and can we dye more fabric?’ I thought, ‘You’re killing me. Let’s go home.’ [laughs.] I just love the enthusiasm of a new quilter who has found and loves it. I don’t know–some of them from the time that they walk through the door you know that they are just going to love it and go on with it. I don’t know if I really had that love initially because I had tried doing other things before. I tried everything imaginable knitting, crochet, upholstering, quilling and painting china. Just anything that you can do with your hands short of having a wood working shop, I tried. When I went into quilting I really did not know that it was going to be the thing that I was going to be doing the rest of my life. And then consequently too if I had been home all the time I could have gotten much more intensively into it earlier on as well. I didn’t. I was working full time as a registered nurse at that time so it really was what I could do in the time I had when I got home in the afternoon with the kids around–actually I had two in college at that time but I had Michael who is a handful. A thirteen year old at the time. It took a little bit longer for me to get into it and say, ‘Yes.’ And it took a little longer for me to realize that this was going to–I hate to say legacy but it has turned out to be for me what is me. What I can point to and say, ‘This is Juanita.’ It has given me more rewards and feeling of satisfaction than being a wife, being a mother and being a nurse because even all of that in the end if it was all I was and I don’t know if anybody but my children will remember me 15 years from now but I’m hoping 50 years from now that someone could pick up one of my quilts, find my name on the back of it and say, ‘Juanita Yeager from Kentucky. Oh, she made this in the year 2000 or 1999,’ and will know that I as a person lived. I as a person, not as a nurse nobody would know or had anything to leave as a legacy. I didn’t start the Red Cross or anything major like that.

KM: So in what ways do you think quilts have special meaning for women’s history in America?

JY: I really think if you follow–if you took quilts from where they started they truly parallel American life period. They parallel the migration. They parallel the economic times. They parallel the political climate. They parallel your graphic area. Where you live. The quilts that were made in the South are very much different from the quilts that were made in New England. The quilts of the Victorian era with the money and the excesses were different–from maybe the quilts that were made in the plains for comfort and warmth. The colors of the 1930’s were certainly happy to kind of dispel the fact that the country was going toward the Depression. It really is a good documentation of us and I don’t know if there is anything else that could do as well as quilts if you truly follow quilts they follow the Industrial Revolution as far as the fabrics. The quilts, the fabrics, the textiles being made at home and or locally quilts parallel where and when the making of commercial fabric and the availability on the larger scale as a commercial product. Quilting certainly has meant for a lot of women economic freedom because it has been a source of income where they can take their talents to teach, to open a shop, to start a quilt show, to being very independent as far as their economic well being is. I just think–in studying quilts you can see 500 years or more ago and 500 years from now [laughing.] there will be a history with documentation for someone studying us as we are now they would have a really good view of what we were as a people.

KM: So how do you think your quilts reflect your community?

JY: I have to say my quilts reflect who I am and where I am. And it reflects my beliefs. Reflects the fact that I was not raised to be an ethnic person. I was raised to be [Marti Plager who was also present says something but it is inaudible.] an American person with a love of beauty and even though my mother isn’t frou frou into doilies and lace. You know that sort of thing but she loved flowers. She loved orderliness and she always taught us to do the best we could do, be the best person we could be and she always championed whatever causes you went about. She was very encouraging in that regard. So I would just say that if you were not just looking at me and looking at my work I think you would probably say I’m a person of the black community. I don’t have any stories to tell. I don’t have any causes to champion. I don’t have–there are a lot of quilts that are made for those reasons because someone wants to put forth an idea even to quilter back into the old days did with the “Fifty-four, Forty or Fight.” Those black and other women probably had some statement they wanted to make that could only be said through a quilt because they certainly couldn’t get out into the county square nor politic for a certain person. They probably could in their bedroom with their husbands at night but they probably couldn’t make the community hear them. I find that I don’t need my quilts as a platform to make my voice heard. What I use my quilts for is simply my way of expressing my creativity, my love of color. The fact that I quilt with passion, do something productive with my life, use the talents that God gave me, gifts that if squander I would not feel I have lived life fully as a person for what He wants me to do. And I really think He wants me to do this. He has made it so easy for me in providing the people around me that give me the support and providing me with the facilities, the supplies. Made it easy for me to go on and find the knowledge that I needed to further what I am doing.

KM: How many hours a week to do quilt or a day?

JY: Eight in a day. [laughs.] It depends. If I wake up with an idea of a quilt in my head [clears throat.] I’m subject to come out of my bedroom without brushing my teeth and go to my studio and start to work. I could well be in there a good long time. My husband use to come to the door 9 o’clock at night and just say, ‘Are we eating today?’ [laughs.] Very nicely. So I would say that some days I can’t get there just because of circumstances won’t let me get there. Then there are some days that I’m there all day from the time I get up and have breakfast until late at night, some times until wee hours of the morning and that sort of thing. I do know that if I don’t get to work, if I have not touched fabric for several days, I get to be a very nasty person. [laughing.] You don’t want to be around me if I can’t get to my quilting. So it varies. It depends on just how involved I am with a piece. I’m really much more engrossed with it as I’m trying to work out all the technical details like the colors I want to work with to make sure that–once I know the fabrics are going to work. Once I get to that stage I’m not as obsessed and then it’s just a matter of at that point of saying, ‘Yes I want to complete it.’ Therefore I will just go at it. It also depends on if I got it promised some place and how much time I have to put into it to complete it.

KM: Like a deadline.

JY: [laughing.] Yeah, right. [laughing.] Nothing like a deadline.

KM: Is there anything else you would like to share?

JY: Oh, no. I think that pretty much covers it. I think I’ve talked quite a bit. [laughs.]

KM: Thank you very much. I really appreciate your doing this.

JY: You’re welcome.

KM: We’re going to conclude our interview now at 5:51.