Karen Musgrave (KM): This is Karen Musgrave and I am conducting a Quilters’ S.O.S. – Save Our Stories interview with Terese Agnew. Due to circumstances this interview is being conducted online. I am thrilled to be interviewing her. We are beginning our interview on March 26, 2006. Terese, tell me about the quilt you selected for this interview.

Terese Agnew (TA): About five years ago, a friend of mine invited me to go to a talk with two young garment workers from Nicaragua and their host, Charlie Kernaghan from the National Labor Committee. They described working under horrible conditions at a factory that produced clothing for export to the United States. My reaction might surprise you though. Here were two very young women who had been subjected to unimaginable abuses but had still found the courage and where-with-all to speak out about their situation in a foreign country! They said they were proud of their work but they wanted to be ‘treated like human beings, not animals.’ I had nothing but admiration for them; their strength and personhood was unforgettable. I wanted to do something to help but I didn’t know what.

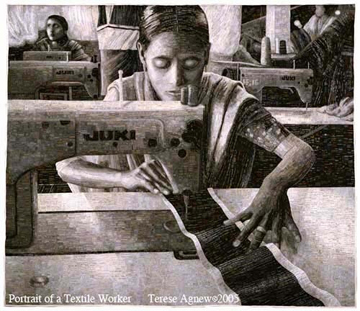

Then one day while I was shopping in a department store, I noticed huge signs everywhere–Calvin Klein, Tommy Hilfiger and so on. They were all proper names. I realized that by contrast, the identity of the workers who made those clothes was rarely thought of and often deliberately hidden. I thought that by creating an image of one of those workers using the name-brand labels on the clothes we buy, I might make it harder to forget the person(s) who makes those clothes. I contacted the National Labor Committee and asked if they had any photographs of textile workers that I might use for the project. They had hundreds. I was looking for one that commanded the same respect that I felt for the two women I had met. I didn’t want people to feel pity. I wanted them to see the potential of a generation being wasted. I wanted people to see a beautiful, dignified young woman who, at the very least deserved to be treated with common decency. I chose a picture that was taken by Charlie Kernaghan of a young garment worker in Bangladesh. I think she is very beautiful; she reminds me of my niece Natasha who will head off to college next year.

The project began with a massive campaign to get the labels. I started with the Milwaukee County Labor Council, a website, and pretty soon the word started spreading. The Sharon Lynne Wilson Center for the Arts in Brookfield, Wisconsin asked if I would like to have the opening exhibit of the piece at their center and I said, ‘yes.’ They assembled a team of wonderful people who continued to collect labels for the project until its completion. I received labels from all over the country, many from around the world and from people across the political spectrum. Every package I got amazed me-people took the time to painstakingly cut out labels-one by one. Quilters and sewers were of course particularly generous and helpful. I loved the camaraderie they shared with me.

KM: This is truly amazing. What was Charlie Kernaghan’s reaction to the quilt?

TA: Oh, thank you for asking that. Here’s what happened: Charlie came to Milwaukee with two textile workers from Bangladesh and a translator. They were on a national tour to tell people what was happening to garment workers in Bangladesh. (BAD.) I was nearing completion of the Portrait, so after their talk at Marquette University they came over to my studio. Both of the women were young and very graceful and understandably angry and sad in their talk. When they came in and saw the piece, it was one of those moments when no words needed to be exchanged, they just got it. They knew that I and everyone who had contributed to the piece appreciated them. They both hugged me and I wanted to show them just how many people cared about their plight so I started carrying in box after box of envelopes that were sent with labels for the quilt and letters! Art is a form of communication and I’ve always believed it should be a two-way street but this project became a four-way intersection with intercepting paths fanning out across the globe.

Charlie said he loved it and asked me a string of very smart art related questions too. He wanted to know how I created the feeling of recessionary space and how that collapsed into labels at a certain distance from the quilt. Charlie’s a great observer of many things or he could never have taken the poignant photograph that this portrait was based on.

KM: Well, this is perfect because I did want you to explain more about the use of labels. How was it working with them? How long did it take you to get enough to finish the quilt?

TA: I used the labels in numerous ways to create the image. For example, I used text on a contrasting background as a gradation (such as white on black or black on white), text borders were ironed back leaving a unified block of tiny words to form specific tones, names were used as segments in a line and combined with others like lines in a drawing. To make her soft (in labels) the gradations had to be very subtle. Charlie’s photograph, beautiful and poignant though it is didn’t have detailed visual information at the scale I was working in. I redrew most of it to articulate details that were incomprehensively fuzzy blown up and to accommodate the directionality of label lettering or their ability to become flat tonal planes. I worked a lot on the light quality too. My goal was to render the image so that people would see it as a representation of a real place from a distance of 15 or 20 feet but maintain the experience of seeing it up close as a mass of labels that could easily be from the clothes in your own closet.

As to your other question, I needed labels up to the end. In fact, I was so desperate for dark gray labels at the end that a few of my friends allowed me to ransack their entire closets. Luckily by then I was pretty good at removing labels without poking holes in a shirt or sweater.

KM: This is so incredible. I truly wish I could see it in person. Where is the quilt now? Where has it been?

TA: Right now it is hanging at the Marcus Center for the Performing Arts in Milwaukee. The opening exhibit was at the Sharon Lynne Wilson Center for the Arts in Brookfield, Wisconsin (January ’05) then it went to the James Watrous Gallery in Madison, Wisconsin (Wisconsin Academy of sciences arts and letters), in February of 2005. This past September it was in a show at INOVA (Institute of Visual Arts) at the University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee. The INOVA show was for The Greater Milwaukee Foundation’s Mary L. Nohl Fund Fellowships for Individual Artists. (I won one of the 3 Established Artists awards in 2004). If people want to know where it will be they can check my website (www.tardart.com). The next showing will be back at the Sharon Lynne Wilson Center for the Arts in Brookfield, Wisconsin for their state wide Hidden River Festival September 22 -24. A few weeks later it will go to Mount Mary College for a symposium

On Portrait of a Textile Worker, and the issues it raises.

KM: As I recall, you began your art career as a sculptor. How did you come to make quilts? And how does making quilts relate to your sculptures, if they do?

TA: From 1985 to about 1989 I made large-scale public sculptures with the help of many, many people but by 1989 I felt that the process worked better than most of the art. I decided I had to rethink everything I’d been doing up to that point. I started wondering how to take issues outside of the narrow political framework of predictable oppositions and put them back into the realm of human experience with art. A lot of political art at that time was very confrontational and ended up preaching only to the converted. After a great deal of contemplation I thought, ‘Why would you oppose anything if you didn’t first value or love whatever was being subjected to destruction, injury or ruin? The emphasis was on the wrong thing!’

By chance in 1992, I’d also been making quilts. At first to stay just to stay warm in the drafty building my husband, Rob Danielson, and I had just moved into. But I quickly saw that using the medium to make art opened up an endless variety of construction methods with a vast range of materials. I started working with fabric scraps and thread the way I would have used line and color in a drawing or painting. Quilting had obvious possibilities as a three-dimensional medium too; sometimes I would tack the fabric on with a single stitch so that it would float on the quilt surface, other times I would unravel the cloth for texture.

Quilts have a warmth that isn’t just about utility. It’s a medium that reminds us of being cared for, and/or it’s opposite; disregard for people and the nature that sustains us. It turned out to be a great way to address political issues without the divisive go-nowhere arguments that dominate mass media. But I’m getting off the topic of your question. My next piece will be perceived as more of a sculpture than a quilt, but it comes from one of the basic definitions of a quilt: three layers; consisting of cloth and batting connected together.

KM: Tell me more. I’m especially interested in hearing your thoughts on this and where you think quilts will be in the future. [there was a long break between this question and TA’s answer due to her schedule.]

TA: Well I’m not letting the cat out of the bag quite yet but I will tell you part of the concept: quilts tend to be 3 layers as I mentioned, but why stop there? Why not make one that’s thousands of layers and build an image from the side? That’s the idea I’m working on.

Where do I think quilts will be in the future? Where ever quilters want to take them. As far as I’m concerned the sky’s the limit.

KM: I agree that the sky is the limit. I just attended the International Quilt Festival in Rosemont and was pleased to see the limit is being tested and accepted into the show. What do you think makes a quilt artistically powerful?

TA: I don’t want to segregate quilts in answering this question. Any work of art that’s powerful for people will be compelling on many levels. Form, composition, what something is made of and how it is made become inseparable from the overall concept. Andy Warhol’s serially printed soup cans stop people in their tracks for this reason. It’s a perfect reflection of the impact contemporary production has on our everyday lives. It makes us conscious of details in our surroundings as opposed to reducing them to ambient background. One of my favorite artists is Roger Brown, who would have made a magnificent quilter had he not been a great painter. His paintings are just beautiful. He works with repetition and pattern to show evocative situations that are as familiar as they are alien. His paintings are more like questions or investigations-that’s certainly part of their power for me.

KM: I’d like to go back to your quilt. It’s quite large 8 feet by 9 feet. Why did you choose to make the quilt this size? Do you usually work large?

TA: I once said “Portrait of a Textile Worker” is just big enough to compete with those Tommy Hilfiger signs. But I don’t think I work that large. Everything I make relates to human scale-I consider how a person would see a piece from a distance and up close. I don’t want my work to overwhelm as much as draw you in. They might seem large because the details are small. I’m trying to show something of the complexity of the world-it’s a very rich place-nothing looks air-brushed to me.

KM: I hope that you and your quilt continue to do good things. Thanks for agreeing to do this interview. The interview concluded on June 19, 2006.