Tomme Fent (TF): This is Tomme Fent. Today is Saturday, December 10th, 2005, and it’s 1:06 p.m. Central Time. I’m conducting a telephone interview with Pamela Allen for the Quilters’ S.O.S. – Save Our Stories project. Pamela is in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, and I am in Sioux City, Iowa, in the United States. Pamela, thanks for agreeing to talk with me today.

Pamela Allen (PA): Oh, you’re welcome, Tomme.

TF: I really want to talk about your very unique style of quilting as part of our interview today. Maybe you could tell me a little bit about how you got into quilting in the first place. I know you had a lot of prior training in other media.

PA: That’s right, I–in fact, I’ve been an artist for about twenty-three years and have worked in lots of different media and in the last, I don’t know, ten years I was doing lots of paintings and collages that frequently, when I looked at them, I thought, ‘Gee, you know, these looks like quilts to me.’ But the down side was that I had no experience in sewing, so I kept putting it off and putting it off until I discovered Lucky Shie, who’s my hero. She’s a fabulous fabric artist who offers a five-day workshop art camp. So I went there, told them what I was doing and what I wanted to do, and her advice was, ‘It doesn’t matter what you do as long as it doesn’t fall apart.’ So I came back after five wonderful days and just started sewing on my thirty dollar church basement sewing machine. And that’s essentially how my work sort of translated from painting collage into fabric collage.

TF: Well, your quilts are really unique. One of the things you do that other quilters don’t do is you use a lot of unusual materials in your quilts. How do you get all of those unusual materials to stay on there?

PA: Well, I have this theory that if you can drill a hole in it or if you can–if it’s metal and you can use this little gizmo I have to make a hole in it, then you can sew it on your quilt. So having come from a background at one time of making what I call ‘junk art,’ which is really assemblage art, I had masses and masses of interesting artifacts and found objects already in my studio, and I just began sewing them on my quilts. They do have significance for me, but they’re not necessarily significant to the viewer, they won’t have the same significance to the viewer. But it just keeps me interested in my quilt as I’m working to embellish.

TF: For example, let’s talk about the quilt that you’ve chosen as your touchstone object today. What’s the name of the quilt?

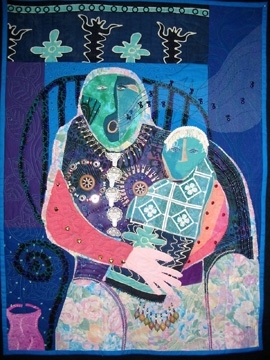

PA: It’s called “Grandmother’s Lullaby,” and there’s a significance to that in that I’m a grandmother even though I’m not a mother, and I have fifteen grandchildren, so this is a somewhat autobiographical quilt. It just shows a woman singing to an infant.

TF: When did you make this quilt?

PA: I made it quite recently. It’s 2005, but I believe it was early in 2005, in January. The significant thing in–it’s a milestone quilt for me because it’s the last quilt I ever made that didn’t have a proper binding on it. [laughter.] Since then, I learned to make a proper binding.

TF: So you said that the materials that you use often have significance to you. How about some of the materials you’ve used in this quilt? I see bobbins and spools and garters and clothespins and keys.

PA: Exactly. They’re kind of, sort of autobiographical things, and very literal in many cases. The bobbins, the little spools of thread and so on, are just making reference to the fact that I now sew. It’s also a generic thing because many, many women sew, and the history of women is that we provide our families with clothing or linens and so on, so it has a larger historical meaning for me. The keys around the neck are reference to a woman’s role as chatelaine. Even in medieval times, she may not have had too many rights of her own but one of the rights she did have was that she was the keeper of the keys of the household, so that’s the reference around the neck, plus it’s very decorative. The clothespins also, again, are a reference to a woman’s role as the laundress. The little wheels around the breasts are personal for me because I moved a great deal when I was a child and it was an unhappy thing for me and I often put wheels in because of the transitory nature of life. Now the garters, everybody always laughs at the garters, if they’re women of my age which is middle age, because we remember having to hold our stockings up with these awful garters. And I actually find them humorous and decorative at the same time. Now the eggs at the bottom are, again, a very literal reference to the function of woman, and in this case especially because it’s a grandmother and child. But, of course, this refers to the fertility of a woman.

TF: Why did you choose this particular quilt for your interview?

PA: I feel that it’s pretty stereotypical of the work that I do. Some of my quilts aren’t as embellished as this one is, but many of them are, and I think I, personally, get a lot of satisfaction and pleasure out of embellishments and I think viewers do, too. They always tell a little story and the viewer brings their own story to it, but I bring a story to it which keeps my interest in the work as I’m working upon it.

TF: I see in this quilt both machine and hand quilting. Is that typical of your style?

PA: Yes, it is. And again, the hand part, the hand appliqué, does come from Lucky Shie, in that this is her style, as well, and I really, really like introducing this coarser, linear element to my work with bright colors of embroidery floss. So, to me, it’s adding a line that scintillates because of its color and unevenness. I also want to introduce the hand of the artist. I want the artist’s signature to be on the quilt and not that mechanical stitching quality that a machine gives you. But on the other hand, the machine quilting is also important to me because it’s free-motion. I can do whatever I want. I can put–I can literally draw on the quilt with my machine stitching.

TF: You also draw, if you will, on your quilts by the great variety of fabrics, not just prints but the different types of fabrics you use. Where do you get the materials that you use for your quilts?

PA: That’s right, I do use–I have what I call–other quilters laugh at me because I say I have this pitiful little stash, and by most quilters’ standards, it is pitiful. It’s because I use almost always recycled fabrics. So once a month or so, I’ll go to this thrift shop or go to the Salvation Army and I’ll just go through the racks of Hawaiian shirts and flannels and hideous bridesmaids’ dresses and polyester and rayon, things that traditional quilters really don’t normally use. And I have no compunction about mixing fabrics. This one has cotton in it, commercial cotton. It has rayon sarongs in it. It has lace on it. It has upholstery fringe on it for the hair. It’s got netting on it. I just don’t care. If it looks right, I’ll use it.

TF: So how many hours a week do you think you spend quilting?

PA: People often ask me that. I work nine to five, Monday to Friday, in my studio. So I go every morning and I spend probably seven hours there and I come home. But I also do a lot of hand sewing at home in front of the television, and even if I’m traveling, I do it in the airports. I do it on trains and things like that. So I would say more than forty hours a week.

TF: You sound like you’re very disciplined in your business, in working in your studio every day.

PA: I discovered that really early on, that I had to treat it like a job because there was this mystique about an artist, you know going in the garrets and working and being inspired and working, and that’s not the way it is. It is a matter of just working, working, working, working, just as you would with any other career. The difference with me is that I really, really enjoy it, and I have probably lower expectations. I do not expect everything I make to be even saleable, let alone a masterpiece. So I’m constantly producing, but not necessarily work that can be sold.

TF: Did you grow up around quilts? What’s your first quilt memory?

PA: I did not grow up around quilts. As I said, I didn’t really even know how to sew. I made an apron in grade eight home ec [economics] class. It’s the art part of the fabric that appeals to me. It was only later that I discovered, through the Internet, this huge collegiate–college, really, of fabric artists across the world, but mostly in the U.S. and Canada. And it was that arts connection, I think, that appealed to me, so it isn’t the quilts. The quilt part, in fact, has been problematic for me because over time, I’ve had to really improve. I was really terrible, my sewing, at first. And I got a better machine and that sort of thing and I feel now that I’m sort of okay, sewing-wise. So I kind of came at it backwards. I think quilters, art quilters who started out quilting try to get out of the box and into the art quilting. I came out the other way and I’m trying to get in the box, in the quilt part of the box, just through my skills and my techniques.

TF: Have you ever used quilting to help you get through a difficult time?

PA: Oh, yes, yes, indeed. And that was the other thing that surprised me when I switched over to fabric because I’m kind of a very lively, up front, kind of hyper sort of person, and I would not have thought that I would have the patience to sit and sew as much as I do, but in fact I discovered it was very therapeutic and it was relaxing, and you sort of go into a Zen mode and creatively, it gives–when you’re doing the hand bit, you’re trying to think about what you’re going to do next and so on, and as far as the therapeutic part, because I work kind of–my subject matter comes from my own life and so on, it’s kind of inevitable that–this year, because my mother died and my sister got cancer, although she’s now in remission, and it’s just been a rough year. And many of my quilts helped me through that because the subject matter of the quilts were about that.

TF: What do you think makes a quilt artistically powerful?

PA: Well, there are two things that I want to see in a work of art, and I’m talking as a work of art, not a quilt but as a work of art. I want to see the hand of the artist. I want to see the personal process of the artist actually working upon the material. And I also want a personal input into the subject matter. Now, there’s a lot of discussion about being derivative and having other artists influence you and so on, and I am a hundred percent with that. My work has Picasso influences in it, Matisse influences in it, and so on, but I try desperately not to copy or not to appropriate, and that’s what I look for in other art quilts is that personal injection that I know that this person has done something no one else has done.

TF: Do you also make any other fiber art objects, like wearable art?

PA: I don’t, actually. I was the kind of person who, when I tried to sew clothing, I’d always put the left sleeve in the right armhole, that sort of thing. It’s funny because when I think about it, it sort of goes against my personality. It’s following a pattern. I’m just not that kind of person. So to me, the spontaneous way that I work is perfect for me, and I think that’s why I don’t do clothing or anything that has to fit.

TF: Well, I know that you’ve started doing some traveling to teach classes and give lectures to guilds and things like that. How is that affecting your work?

PA: How is it affecting my work? That’s interesting. I think as for the content of my work, I’m not sure it affects it all that much, but what it has done is made me very, very happy to have found this genre. The more people I meet, the more I teach, the more traveling I do, I’ve discovered that it’s a huge–I was going to say sisterhood, but there are many men in this. It’s a collection of like-minded people who are so generous and fun and we share common experiences and that’s really affected me in my teaching and so on. I enjoy teaching, so that’s also good.

TF: In what way is quilting important to your life and how does that differ from other types of art that you’ve done?

PA: I think it doesn’t differ from other kinds of art, but I feel as if I’m–I feel as if I’ve found my niche with quilting. So whereas before, I was often anxious and worried about, you know, ‘I’m not as good as everyone else,’ or ‘I’m not on the cutting edge,’ and all that sort of stuff, that all went out the window when I discovered working with fabric for the certain reasons that I mentioned before, that it’s–actually it’s relaxing and it makes me happy, but also because I just enjoy it so much. I really enjoy going to work each day. I think about what I’m going to do next. When I come in my studio, I’ve got lots of colorful fabrics around and past-made quilts that please me. So I think that’s that same thing.

TF: You mentioned that you don’t follow a pattern and you do really free-form work. What suggestions would you have for quilters who haven’t tried that type of work that would allow them to become a little more free.

PA: Yes. It’s not a matter of technique. Even now, I try to analyze my own way of doing things, and it’s not technique, it’s attitude. And it’s sort of ‘in your face’ attitude, in a way. Like, ‘Take out the fabrics, throw away your rotary cutter, use your scissors as if it were a drawing tool, and just lay your shapes,’ and just confidence that, ‘Oh, if that doesn’t work, take it off, put something else on, or if some of it works, put something else on the part that doesn’t work.’ Just the confidence that eventually, it will work. And you just sew away and you quilt it and you are happy with it. It sounds pretty simplistic, doesn’t it?

TF: It makes it sound very easy to do. It makes me wonder why more people don’t give it a try.

PA: I wonder, too, sometimes, because quilt–now I do make a distinction between quilters and art quilters, and art quilters presumably are making art and a function of making art is to open up their mind and to be–I call it ‘stream of consciousness.’ You do one thing which suggests that you might do something else and then that suggests that you might do something else, so it’s always a creative and open-ended process. And when people get bogged down with, ‘I’m making this plan, I’m cutting out templates, I’m arranging it on my background fabric,’ it seems to take all the spontaneity and creativity out of it. Now, I couldn’t possibly work that way. I think others might benefit by sort of throwing out the templates once or twice and their patterns once or twice, and just sort of go with the flow, cut with scissors, choose the colors you like that aren’t on the color wheel, and that sort of thing.

TF: Are all of the quilts that you make for display, or do you also make quilts for use, like bed quilts and lap quilts?

PA: Yes, well, I would say all of my quilts are for display. I have made two quilts for snuggling and I vowed that I would never do it again. And the nature of the way I work, because I do raw-edge, hand appliqué and so on, the one I made for myself to sort of snuggle under for television, when I wash it, it becomes more and more and more like chenille. And the mixture of fabrics I use, they’re not all washable, so that has deterred me from doing bed coverings.

TF: Have you made quilts for friends and family?

PA: I have, yes. I do smaller things, but I do things. We have a huge family and we’ve got twenty-five people on our Christmas list, children mostly, and I have done things for them, yes, mostly things like appliquéd sweatshirts and appliquéd aprons and things like that.

TF: How do you think quilts are significant in either reflecting or preserving women’s history in North America?

PA: It is significant. It’s something I’m reluctant to accept, actually, because it’s so stereotypically women’s work, to work with fabric and sew and so on. But in the art quilt genre, anyway, I would say that we are continuing the tradition into the modern era in that now, it’s not necessarily, what’s the word, functional, but rather an expression of – any artist, an expression of how you feel or how you think or what message that you want to give to people. And it’s in a particular genre that’s particularly feminine and has been for decades and centuries. So I’m aware of that and I’m quite charmed by that.

TF: Do you have any sense of where your work will fit into the bigger picture of art history?

PA: My work?

TF: Yes.

PA: I don’t know, I think I’m more humble than that. I think my work is art, I do think it’s art. I’m sort of not too humble about that. But whether it’ll make a significant difference, perhaps to the owners of each one, it might, but I don’t think over a long–just as many painters and many printmakers and many other artists in other genres are not going to make a huge impact, they’ll make an impact on the owners of their work, perhaps, and if they teach, they’ll make an impact on their students and the up-and-coming generation. And I do hope that I can make that kind of impact on my students. I have been to enough shows now to realize that–some of the women come up to me afterwards and sort of thank me for freeing them, so I think there’s a niche there that I’m filling, yes.

TF: Well, I think your work is amazing and I think it is very important in the history of quilts and will be studied and enjoyed for years to come.

PA: Well, thank you very much.

TF: Is there anything we haven’t talked about that you would like to talk about in relation to quilting? [pause.] What about the computer, do you use the computer to aid you in design or in any other aspect of your work?

PA: That’s a good point. I do indirectly use the computer and actually directly, now that I think about it, because I–this technology where you can use this Bubble Jet Set to prepare your fabrics to take on a computer image, I do use that and I think it’s brilliant, actually, and maybe could be used a little more adventurously by other quilters, as well. And I was also toying with digital collaging and things like that before I began quilting, and I refer to those frequently in designing quilts. My memory of that sort of funny juxtaposition of different shapes and different scales, oddball color and so on, is very available on the computer and that’s why I loved doing digital collage, and I think that did, indeed, affect my imagery in my quilts. And also being on the Internet and talking to other artists, other quilt artists, is a great tool for an artist because essentially, you work in an isolated place as an artist. You’re in your studio and you don’t sort of face-to-face meet people, but having those thousands of people on the Internet who are interested in what you are interested in is marvelous. It really keeps you connected.

TF: Well, I would like to thank Pamela Allen for allowing me to interview her today as part of the Quilters’ S.O.S. – Save Our Stories project, and our interview concluded at 1:30 p.m.

PA: Well, thank you, Tomme.